Eventually, age catches up with you.

St. Marys Challenger lived up to its name by defying that assertion longer than its counterparts. But after 107 years, the laker was taken out of service in November 2013 to be converted to a barge. Built in 1906, Challenger was the oldest operating freighter on the Great Lakes.

The decision to convert the 551-foot cement carrier followed a series of upgrades spanning several decades, including extensive hull rebuilding, installation of a self-unloading cargo system and a myriad of other structural upgrades. In the end, the owner was left with a Skinner Marine Uniflow four-cylinder reciprocating steam engine burning heavy fuel oil, outdated DC electric and an aged mechanical propulsion system that made operating the boat an ever-increasing expense.

“The problem was anything that broke, anything that needed to be worked on, was absolutely custom,” said Ed Hogan, vice president of operations for Port City Marine, which owns the vessel. “If we needed a piston ring, it was a custom piece. Everything had to be done by machinists, so it was really expensive to maintain. Every spring, it got harder and harder to get things going, because even a minor glitch would be a no-sale item.”

|

|

The laker arrives at the mouth of the Calumet River in South Chicago, Ill., in 2005. |

Repairing an older vessel can be a great burden for owners. SS Badger is the last remaining coal-powered ferry operating on the lakes. When it’s in need of repairs, parts are taken from its twin ship, SS Spartan, said Caitlin Clyne, registrar and collections manager at the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc, Wis.

Port City Marine, based in Muskegon, Mich., considered its alternatives, including retrofitting Challenger with a diesel engine. Not only would that have cost about $20 million — nearly double the barge conversion project — but it would have saddled the company with ongoing expenses. And while a crew of 25 was needed to operate Challenger, the articulated tug-barge (ATB) can operate with 11.

The company will also save money on fuel, as the vessel burned a considerable amount even just sitting at the dock, Hogan said.

Aging machinery and stricter fuel regulations, coupled with would-be requirements following Challenger’s five-year mandatory inspection this winter, led the owners to decide on conversion to an ATB. It was the most cost-effective option, Hogan said.

“If we were to have kept the boat the way (it was), the vessel wouldn’t have lasted,” Hogan said. “You were at risk of having something happen that puts you down. The bottom line is we’ve got to move cement and it’s got to be productive.”

In November, Challenger took its final self-propelled voyage from Chicago to Bay Shipbuilding Co. in Sturgeon Bay, Wis., blowing its steam whistle and flying a white flag as it arrived.

Historical artifacts, including the wheelhouse and engine room telegraph system, were removed and are expected to be donated to a museum.

Asbestos was extracted from the boiler, and bunker tanks were scrubbed clean. The crew quarters, boiler, engine, generators and piping and plumbing apparatus were stripped from the vessel, along with flammable materials.

|

|

The deck crew uses a bosun’s chair to lower deck hands to the dock for line-handling operations. Bosun Dave Knuth, right, gets ready to swing the boom out. |

The fore and aft superstructure was removed before torches helped cut off the stern while the boat was still in the water.

“If you look at a side view of the vessel now, they cut in the fuel bunker area down to about three or four feet above the waterline and then they worked aft and took the whole thing off,” Hogan said in February. “So there’s a big empty void back there — there’s no sides, no deck, no ceiling, but the bottom of the boat is still there. The propeller is still hanging off the end.”

The remainder of the stern was to be removed after the ship was placed in dry dock in March. Bay Shipbuilding will then attach a new stern that’s being fabricated in several pieces.

The ballast system, which was steam-powered, will be completely replaced to meet modern construction requirements.

After the work is completed and Challenger returns to the Great Lakes, it’ll be pushed by Prentiss Brown, which currently powers St. Marys Conquest, another Port City Marine vessel that was converted from a steamer to a barge in 1986.

“We have a second Bludworth tug — the Bradshaw McKee — that will push the Conquest,” Hogan said. “Both tugs will be completely interchangeable.

“It’s really the only way to go.”

The ATB will burn much cleaner fuel, and the owners expect it to carry more cargo. The owners won’t be sure how much until construction is complete.

|

|

Demolition of Challenger’s lapped-and-riveted counter stern is nearly complete at Bay Shipbuilding in January. The process was necessary to prepare the vessel for service as part of an articulated tug-barge. |

Expected to return to the Great Lakes by June, Challenger will maintain its name, and will continue to carry powdered cement from St. Marys Cement Co.’s elevator in Charlevoix, Mich., to South Chicago, Milwaukee, Manitowoc, Wis., and Grand Haven, Mich.

Capt. George Herdina, of Sturgeon Bay, recalled maneuvering the laker through the canals of Chicago with machinery from a bygone era.

“There were a few times we lost the steering,” said Herdina, who spent 19 years as captain of the ship before retiring in 2009. “You’ve always got an engineer at the throttle in the engine room on that, because it’s not automated.

“I think you just have to realize it was a 1906 vessel. It’s not as seaworthy as the ones that are built in the ’50s or ’60s or ’70s. You can only do what you can with the equipment you have.”

|

|

Challenger’s pilothouse is lifted intact from the forward end. The structure and its contents will be displayed at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio. |

Many companies decided to scrap freighters like Challenger in the ’80s for more modern vessels, said Clyne.

“We are seeing the end of it,” Clyne said of steamships. “There are a couple steam-powered freighters on the Great Lakes, but none of them are currently working. And they have lighter steam engines, like a steam turbine.”

Museums are doing their part in preserving the ship’s history. The Wisconsin Maritime Museum obtained several engine logs, deck logs, blueprints and other artifacts before the conversion work began on Challenger.

“Just seeing that last engine log is really haunting,” Clyne said, “because the final note of ‘finished with engines.’ And someone put underneath the notation ‘forever.’ It kind of makes it very real.”

|

|

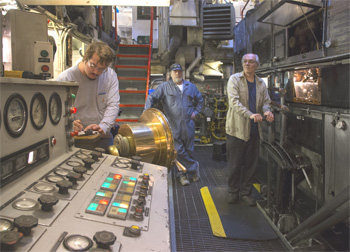

On approach to Bay Shipbuilding, watchstanders wait for final engine orders to ring through on the telegraph. It was Challenger’s last voyage under steam. From left, 3rd assistant Andy Vervelde, chief engineer Dave Jarvis and 2nd assistant Bob Sincavage, who is doing the shifting. |