Foss Maritime Co. took advantage of advances in battery technology when it built its second hybrid tug, Campbell Foss.

The lithium polymer batteries in Campbell Foss, made by Corvus Energy Ltd. of Richmond, British Columbia, are lighter and more powerful than the conventional lead-acid batteries in Foss’s first hybrid tug, Carolyn Dorothy.

Campbell Foss began operations Jan. 29 at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach doing ship assist and vessel escort with containerships, oil tankers and oil barges. The tug joins Carolyn Dorothy, the country’s first hybrid tugboat, which began operations at the ports in 2009.

Campbell Foss was built by Foss Shipyard of Rainier, Ore., in 2005. It is a Dolphin class tug designed by Robert Allan Ltd. The Rainier shipyard also did the retrofit. No changes were made to the hull of the vessel. An azimuthing stern drive (ASD) tug, Campbell Foss is 78 feet in length with a beam of 34 feet. It has two Rolls-Royce US 205 stern drives.

Foss decided to keep the two Caterpillar 3512D engines that were installed in 2005, because they are relatively new, according to Susan Hayman, vice president of corporate development for Foss. Each engine is 2,550 hp providing a bollard pull of 65 tons ahead and 69 tons astern.

The 5,100-hp Campbell Foss has the same hybrid propulsion and energy system that powers its sister ship, but the first tug was a newbuild and Campbell Foss is a retrofit.

Another major difference in the two tugs is the batteries. The second hybrid tug has 10 Corvus lithium polymer batteries, compared with 126 lead-acid batteries on the first hybrid tug. The batteries in Campbell Foss take up less than half the space of those on Carolyn Dorothy, according to Jerry Allen, Foss’s fleet engineering manager for California. The lithium batteries increase the tug’s efficiency.

“The batteries are way more robust,” said Allen. “We can cycle deeper, to a lower state of charge and charge them much faster.” The batteries can be run down to 35 percent before needing to be charged.

Lithium batteries, like the ones in Campbell Foss, are 76 percent more powerful than a conventional lead acid battery, according to an article by Corvus Energy’s CEO, Brent Perry and Chief Technical Officer Neil Simmonds. And the battery is still powerful, even at lower charge levels.

“This means we can operate all machinery until the very end of the discharge life of the battery, even with very large loads, without seeing the battery voltage drop to levels that machinery cannot operate at,” Perry and Simmonds wrote. “Simply put, they push more energy longer, and can do this over and over again.”

The number of lead acid batteries needed to do this would be so high, that storage and weight would be a problem.

Batteries provide a source of power that is more efficient and less polluting than diesel engines that run all the time.

The vessel’s two Rolls-Royce US 205 stern drives can be powered by the two Caterpillar 3512D main engines or by the two 500-kW Teco-Westinghouse motor/generators. The batteries are tied electrically to the switchboard and provide another form of power, in addition to the generators and engines.

The motor/generators are built into the same shaft lines that connect the Cats to the stern drives. Depending on which mode the tug is operating in, the motor/generators can function either as motors or generators.

In all hybrid modes, the motor/generators turn the ASDs. When electricity is used to provide energy to turn the ASDs, the clutch is off for the main diesel engines, Allen explained.

In assist mode, the Caterpillar diesel engines provide energy, through the shafts, to the ASDs. In this case, the two Westinghouse motor/generators are not needed to turn the ASDs, so they become generators and provide ship power, Allen said. The energy travels back from the motor/generators, through the DC bus to provide energy.

“Power flows in both directions in this vessel,” Allen said.

|

|

|

|

The batteries can be charged in all modes. In assist mode, the energy travels from the two diesel engines to the motor/generators, then to the DC bus, then to the batteries.

The vessel has two auxiliary diesel generators, the 125-kW John Deere 6081 and the MTU Series 60 Tier II 350-kW generator, said Allen. They are shut down during main diesel engine operation. Either the John Deere alone or the John Deere and the MTU charge the batteries, going through the DC bus.

The generators are used together in transit two mode (up to 9 knots). Each generator can charge the batteries alone, but the John Deere is used in idle/stop mode. Less energy is required in this case.

The batteries can also be charged by shore power, while the tug is at its berth. That’s cheaper and produces no emissions.

When transiting on batteries only, DC power is supplied to the DC bus and is converted to AC power. It then goes to the Westinghouse motor/generators, operating as motors which turn the ASDs.

When Campbell Foss is in idle/stop mode, battery power is used until the batteries are depleted. Then the John Deere starts, charges the batteries and supplies limited propulsion, said Allen.

The hybrid propulsion system in Campbell Foss, designed by Aspin Kemp & Associates of Ontario in partnership with XeroPoint Energy of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, incorporates several new components in addition to the batteries. They include the two Teco-Westinghouse motor/generators introduced into the two shaft lines and clutches between the diesel engines and the motor/generators to provide different combinations of propulsion, such as mechanical, mechanical-electrical or just electrical, according to Dylan Sheehan, Aspin Kemp’s business development manager.

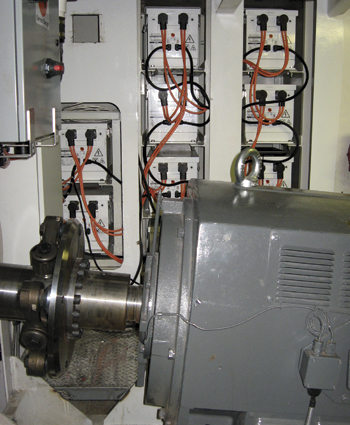

The main switchboard incorporates new components, including variable frequency drives, active front-end converters and DC/DC converters. The DC/DC converters convert and regulate the power supplied from the lithium ion batteries to the voltage requirement of the DC bus, said Sheehan.

Software designed by Aspin Kemp allows the operators and engineers to monitor how well the system is working. The components of the hybrid system are displayed on touch-screens in the wheelhouse and engine room.

Aspin Kemp also builds the energy management system, which controls the different power sources to create the most efficient operation. “The redundancy and reliability of the hybrid system design minimizes the unnecessary operation of multiple and large engines and permits single or auxiliary engines to power numerous loads,” Sheehan said.

A conventional tug has an inflexible power plant, which is not very efficient, given that harbor tugs need full horsepower for only short periods of time. An analysis of operating patterns of two Foss tugs at the ports of Los Angles and Long Beach, conducted as part of the design process of Carolyn Dorothy, found that tugs need full power 7 percent of the time. “That is why hybrid makes so much sense, because you match sources and power needs,” said Hayman.

It takes about half an hour for the lithium batteries in Campbell Foss to fully recharge with the small generator on the vessel when underway, compared to one hour for the batteries in Carolyn Dorothy, according to Allen. Once the batteries are charged, they provide all power when the tug is in hotel mode, said Allen. And the batteries alone can power the tug in idle mode for station keeping when underway. Once the batteries are depleted in idle mode, the John Deere auxiliary generator automatically starts and charges the batteries and also provides limited propulsion, Allen said.

Campbell Foss runs on one diesel generator for transit one (up to 7 knots) and on two diesel generators for transit two (up to 9 knots), according to Allen.

If the main engines are in standby mode and full power is required, the batteries and generators bridge the gap until the main engines are brought online. That gap is about eight seconds, according to Sheehan.

The two hybrid tugs are part of a massive effort by the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to reduce emissions in all facets of operations. Foss received $1 million from the ports for each hybrid tug built as part of this effort.

The bills for Campbell Foss have not all come in, but the cost to retrofit the tug will be about $2 million, according to Hayman. Carolyn Dorothy cost about $2 million more to build compared with a conventional newbuild.

Foss’s first hybrid tug generates significantly less emissions than the company’s conventional tugs. A comparison of two Foss Dolphin-class tugs — Carolyn Dorothy and Alta June, a conventional ASD — showed that the hybrid tug produced 73 percent less particulate matter, 51 percent less nitrogen oxide and 27 percent less carbon dioxide. The data is from a report by the University of California, Riverside.

There’s also a savings in fuel costs. Foss saved 20 percent in fuel costs operating Carolyn Dorothy compared with a conventional hybrid tug, according to the university report.

Another hybrid advantage is in maintenance costs. Right now, it appears that the main engines on a hybrid tug have accumulated about half as many hours as a conventional boat, according to Allen. “This will extend the overall life cycle considerably,” he said. And the generators are much cheaper to overhaul than the main engines, said Hayman.

The lithium batteries are completely maintenance free, according to Ron Burchett, Corvus Energy’s marine sales manager. There is a computer in each battery that continuously evaluates each cell so they maintain the same voltage, according to Burchett. He said the batteries on Campbell Foss will last 20 years.

With the success of Campbell Foss and Carolyn Dorothy, Foss Maritime has plans to covert Alta June to a hybrid tug in about two years, according to Foss spokeswoman Megan Aukema.