Gordon Bain calls his big new tug “the beast.”

Bain is president and founder of Ocean, the Quebec-based marine services company. The official name of his company’s newest tug is Ocean Tundra. At 118 feet in length, this twin z-drive, 8,160-hp boat generates a bollard pull of 113 metric tons. Those stats are the basis of the claim that Ocean Tundra is the most powerful harbor tug ever built in Canada.

However, when Bain calls the tug a beast, he is not thinking about raw power alone, but also the vessel’s ability to perform safely in extreme northern environments. With an ice class certification of 1AS FS, Ocean Tundra routinely performs icebreaking duties on the St. Lawrence River.

“This tug is really a mean machine,” Bain said, recounting a ride he took on Ocean Tundra this winter near the company’s Quebec City base, where the St. Charles River joins the St. Lawrence. At the time, the rivers were encased in ice, including an ice ridge in the St. Lawrence about 15 feet thick. The boat, he said, was able to “crush the ice without any trouble.”

|

|

Capt. Rejean Blais at the controls. |

The boat went through the ice ridge, continued up the St. Charles, then backed out, crushing ice all the way. The ice, he said, went through the propellers of the z-drives “like slush, no noise, no vibration.”

The z-drive’s stainless steel props are just under 10 feet in diameter. After going through the props, the biggest pieces of ice left behind in the boat’s wake were only about 9 inches square, Bain said.

“What comes through the propellers, comes out like that,” he said, making a sweeping motion with his hand. “It outperformed anything I thought it would.”

Ocean Tundra was not designed just as an icebreaker. The company calls it a multipurpose coastal tug capable of icebreaking, ship escorting and docking, firefighting and even some ship rescue or salvage work.

“There are many reasons we built Tundra,” Bain said. “We try to get as much versatility as possible.”

The boat was designed by the Vancouver design firm of Robert Allan Ltd. The initial mandate of the design team was to create a boat with significant icebreaking and escorting capabilities that could work with LNG carriers and petroleum tankers for an extended season in the lower St. Lawrence River, according to Robert Allan, the head of the design firm. However, when various LNG terminals did not materialize, the tug was reconfigured for a more multifunctional role.

While it might not be suitable for year-round operations in the high Arctic, it could work “just about anywhere in the Arctic in the summer and shoulder seasons,” according to Allan.

“This a pretty serious icebreaking boat,” he said. “Within Canada, it could work anywhere in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes throughout the winter…It’s the most capable tug in the St. Lawrence system. I can say that with assurance. Our press release calls it the most powerful tug in Canadian registry.”

|

|

The tug in mid-March on the St. Lawrence River near Quebec City. |

The tug’s z-drives give it advantages in the ice. While a conventionally powered tug will create a channel about the same width as its beam, a z-drive tug can create a path one and a half times its beam. By angling the z-drive’s props outboard, the operator can “vector the ice away from the boat.” This also creates a clearer channel behind the tug, as the broken ice pieces are pushed below the adjacent ice sheet.

Yet another advantage is the ability of the z-drive to generate almost as much thrust in reverse as ahead. When moving astern, Ocean Tundra can exert 95 percent as much thrust, while a boat with a prop in a fixed nozzle can exert at best 50 percent. So a tug like Ocean Tundra is much less likely to get stuck in the ice, and when it does, it can extract itself more easily.

“We know from a lot of experience and model testing, z-drives are a huge advantage when you’re working in ice,” Allan said.

|

|

The towing pin system and stern roller. |

Ocean Tundra also needed to be able to escort large tankers and bulk carriers. “The biggest challenge for us was to combine high icebreaking capability with a significant escort capability,” Allan said.

The two roles are in some ways conflicting. The ideal icebreaker has a bow that allows it to ride up on the ice, while an escort vessel needs to have a hull that can generate powerful lateral forces, especially focused on maximum area low and forward in the hull.

|

|

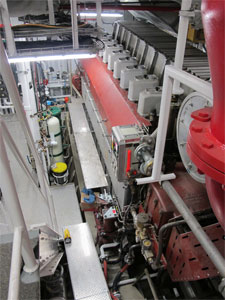

The tug is powered by two 4,080-hp MAK 9M25C diesels. |

“You should move the center of effort as far forward as possible,” Allan explained. “The centroid of all the underwater area is as far forward as practicable. That’s what generates the indirect forces. However this is directly contrary to the form for most efficient icebreaking, so a delicate balance is necessary between these two contrary design objectives.”

The problem is not a new one for the design firm. Robert Allan Ltd. designed four similar tugs for escort work at a Russian LNG terminal on Sakhalin Island in the Pacific, a place with what Allan called “a pretty high ice regime.”

Ocean Tundra is a “slightly scaled-up model” of a “well-proven prototype,” Allan said.

Central to the boat’s duties are its winches, which must operate reliably in a very challenging northern climate.

On the bow is a Markey DESDF-48 200-hp electric escort hawser winch with render/recover capability. The winch has a 202-metric-ton pulling capacity and 307-metric-ton braking capacity. The brakes and clutches on the winch are actuated by a pneumatic system.

Markey came up with several modifications of its standard designs to ensure reliability in extreme cold. Ocean Tundra’s escort winch has an attached heated enclosure to protect those items that could be affected by the cold. They include the electric motor, water-cooled slip-brake, pneumatic logic panel and lube pump.

“The most vulnerable elements are housed in a nice environment,” said Scott Kreis, Markey’s vice president of sales.

|

|

Ocean fabricated a Plexiglas cover to protect the Plasma lines. |

The winch is lubricated with synthetic oil suited for cold-weather operations.

“We added the heater and special oil for the gearbox,” said Blaine Dempke, Markey’s president.

Ocean added another structure to protect the bow winch from the elements. Ocean created a shield to keep snow off the double-drum winch. “Once the winch was placed on board, Group Ocean did cover the drum areas with clear Plexiglas panes,” said Kreis. “They did a good job so it sheds snow properly.”

To increase the versatility of the boat, Ocean wanted Tundra to have a towing winch. And to protect the towing winch from the weather, Ocean wanted to fit it inside a protective housing. Once again Ocean turned to Markey.

The towing winch is a Markey single drum 125-hp model TES-40UL with a braking capacity of 276 metric tons and a pulling capacity of 66.7 metric tons.

“We designed the towing winch to fit in a house,” said Dempke. To fit inside the house, it had to be very compact, about 10 feet long instead of the more typical 12 feet, said Dempke, who described the stern winch as “highly customized.”

|

|

On the bow is a Markey 200-hp electric hawser winch with two drums, one for escort and the other for docking. An attached heated box protects weather-sensitive elements. |

The stern winch’s enclosure is an extension of the deckhouse with an opening on the aft side as wide as the drum.

“When the winch is not operating, it can be completely closed off,” said Kreis. “It’s a winch in a room.”

While solving some problems, enclosing the winch in a box created another: the crew’s view of the drum from the wheelhouse is blocked. The solution was to install a camera in the winch house. Through closed circuit TV, “the operator in the wheelhouse can see how (the winch) is operating,” Kreis said.

In addition to the controls in the wheelhouse, the crew also has portable controls resembling large remote controls for a TV, one remote for the escort winch and another one for the towing winch, allowing the winches to be operated locally on deck.

The Tundra specs called for a towing winch with a pneumatically operated brake, but Markey wanted to be sure there was a device that would prevent an unanticipated and uncontrolled release of the wire in the event of an air-line failure. So it wanted to install a manual brake screw as well. But Transport Canada requires towing winches to have an emergency release that allows the wire to free wheel in any condition.

|

|

To protect it from the weather, the Markey stern winch was placed inside an extension of the deckhouse. An aft opening permits the wire to exit on its way to the stern. |

“We didn’t want to get rid of that feature,” Kreis said of the brake screw. So Markey devised an abort system that would free the pneumatic brake and the manual brake screw in a single push of a button.

Markey ended up developing a toggle linkage to solve the problem. When the abort button is pushed, the clutch and band brake release and an air cylinder is actuated to disengage the mechanical lock.

Since Tundra joined the Ocean fleet late last year, its duties have been confined to the St. Lawrence River, escorting and docking ships and using its icebreaking capabilities to keep docks clear for ships.

But Tundra is capable of doing much more. Its three monitors give it excellent firefighting abilities. The boat, classified FiFi-1, could even be used to help out municipal firefighters. For example it has four three-inch hose connections on either side of the boat that local fire departments could use to increase their water supply.

|

|

One of the two Rolls-Royce z-drives. |

No government regulations required the boat to have the external firefighting gear that it does. Bain said, “It’s what you can call a gift for society.”

There is some earning potential there. The towing winch and the external firefighting systems mean Ocean Tundra could engage in salvage work — for example coming to the aid of a ship on fire, putting out the flames and then towing the disabled ship to safety.

Perhaps the greatest potential is in the far north, both in conjunction with oil and gas exploration and for escorting ships as the shrinking ice cap leads to routine transits of the Arctic Ocean by cargo ships.

“We think there are going to be escorts there one day,” Bain said.

Given the pristine nature of the environment in the north and the increasing amount of vessel traffic, the need may arise to station a capable boat like Ocean Tundra there. “They’re going to have to put tugs on station in the north,” Bain said. “It’s an environmental safety tool.”