Arthur Foss is in great shape — for a wooden-hull tug built 125 years ago.

Up until the 1960s, the 120-foot, 700-hp tug earned its keep for Foss Maritime hauling log rafts to lumber mills in Puget Sound. With the advent of more powerful, steel-hull vessels, Foss determined that Arthur Foss had become obsolete. On July 28, 1968, Foss took the tug out of service and two years later donated it to a vessel preservation group.

Today, Arthur Foss serves as a museum vessel. In retirement, it rests at a dock on Lake Union in Seattle, under the care of Northwest Seaport, an organization that has assembled a small fleet of historic vessels.

Arthur Foss boasts of a long and colorful history that in many ways embodies the nautical history of the Pacific Northwest. Built in Portland, Ore., it went into service in 1889 as Wallowa, towing large sailing vessels over the Columbia River bar. After gold was discovered in the Klondike in 1896, Wallowa got swept up in the rush to the north. It began taking barges carrying supplies and gear needed by the prospectors and miners in Alaska and the Yukon. It even towed a paddle wheeler to the mouth of the Yukon River in the Bering Sea so that prospectors could ascend the river in their quest for gold.

|

|

John Gormley |

|

Otto Loggers, executive director of Northwest Seaport in Seattle, in the wheelhouse of Arthur Foss. Loggers hopes that the ongoing restoration of the 125-year-old tug will allow it to voyage under its own power once more. |

When the gold rush ended, the tug began what was to be its primary mission during most of its working life: hauling logs on Puget Sound. But there were two very notable breaks from that work.

First was a stint as a movie star in 1933. In the classic MGM movie Tugboat Annie, which was shot in Seattle, the boat played a central role as Narcissus. Her captain was the Tugboat Annie of the title, played by Marie Dressler. The cast included Wallace Beery and Robert Young.

A decade later, the tug got to play an important role in a real-life drama, World War II. In 1941, the United States had not yet entered the war that was already raging in Europe and China, but military preparations were underway. Arthur Foss was chartered to take materials to the Navy base at Pearl Harbor. When the U.S. was attacked in December, the tug found itself 2,300 miles west of Hawaii on Wake Island. When the Japanese attacked Wake, Arthur Foss barely managed to escape just hours before the island fell.

The primary responsibility for protecting this venerable vessel belongs to Otto Loggers, the executive director of Northwest Seaport. “For its age, she is in extraordinary condition,” Loggers said of the tug. But that does not mean the tug is seaworthy.

As recently as 1984, the tug sailed to Alaska under its own power to mark the 25th anniversary of Alaska’s becoming a state. However, the tug’s current condition would preclude any trip under its own power. “She is not going to be voyaging without her hull being taken care of,” Loggers said.

The hull is sheathed with ironbark, a kind of tropical hardwood, probably Australian eucalyptus. Much of the ironbark is peeling away, especially near the waterline where the nails holding it to the hull have corroded. As a result, some of the most serious rot is in the hull planking along the waterline.

“The plank work is a major priority,” Loggers said, noting that it will probably represent the most expensive part of the restoration.

The boat will have to be dry-docked and the ironbark sheathing removed. Then the exposed planks will be examined for rot. The area around the bow is expected to need the most work. All the sound pieces of ironbark will be salvaged and reapplied once the hull planking has been repaired.

It is something of a wonder that a wooden boat like this that has seen such hard use in its long work history is still afloat. Its current setting is a freshwater lake in an extremely rainy part of the world. The freshwater of the lake means that there are no marine worms boring into its wooden planks and timbers. But the constant rain creates the threat of rot in the woodwork. In fact, during the winter the tug is covered with tarps in a not entirely successful effort to keep the boat’s deck and woodwork dry.

Portions of the wooden deck have deteriorated and need to be removed and replaced. Of particular concern is an area in the bow in the vicinity of the towing bit, where the water tends to pool.

“Creating a watertight deck, that’s the priority here,” Loggers said. In addition, substantial repairs need to be made to the wood of the pilothouse.

The engine, by contrast, is still in operating condition and is in the process of being overhauled. One of the six cylinders has been overhauled and Loggers would like to see the others done at a rate of one per year. But the engine could be used for short voyages even before the overhaul has been completed.

Built by Washington Iron Works in Seattle and installed in 1934, it is not the tug’s original power plant. (The diesel engine had not yet been invented when Wallowa slid down the ways in 1889. The boat’s first two engines were steam-driven.) In a sense, a new powerful diesel engine was part of the boat’s earnings for its participation in Tugboat Annie. “In the process of shooting the film, there was an accident,” Loggers explained, and the film studio agreed to pay for the damage. “Foss contracted with Washington Iron Works to build the six-cylinder diesel, which may have been the largest marine diesel engine of the time.”

|

|

John Gormley |

|

During the 20th century, the tug’s winch was used primarily for towing rafts of logs on Puget Sound. The tug performed this kind of work right up until its retirement in July 1968, when Foss decided a new generation of more powerful steel-hull boats had rendered Arthur Foss obsolete. |

Arthur Foss may or may not have been the most powerful tug anywhere, but it certainly was the most powerful in the Pacific Northwest. And this venerable engine is started up on a regular basis.

While many of the other systems — electrical, fire, heating, piping, dewatering — are operable, they do need to be updated to make the vessel safe and reliable.

“This is not a derelict vessel,” Loggers said. “It’s one of America’s treasures, but she needs help.” He would like to see the tug reclaim some of its past glory by restoring it to operating condition.

“The big goal is to get her out and voyaging once again to the ports she visited, especially the ones in Puget Sound,” Loggers said. “A lot of things need to be done.”

He believes that goal could be achieved in a relatively short time. “We’d like to be able to get underway by 2015,” he said.

All it would take would be money, probably a lot of it. “An endowment to keep this vessel alive for the next generation, that’s what we need,” Loggers said.

One hopeful sign is that awareness of the historic significance of the vessel goes well beyond the maritime industry. The vessel is already included on the National Park Service’s list of National Historic Landmarks. And the boat’s role in the Alaska gold rush of the late 1890s gives Arthur Foss a strong connection to the era that saw Seattle emerge as the pre-eminent city of the Northwest.

“The gold rush was instrumental in making Seattle the city it is today,” said Jacqueline Ashwell, superintendent of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, a unit of the National Parks system located in downtown Seattle.

When the gold fever struck, about 100,000 people rushed north. Of that number about “300 people struck it really rich,” she said, and “50 were able to hold onto it.”

|

|

John Gormley |

|

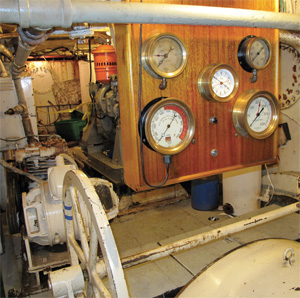

Gauges in the engine room for monitoring the 700-hp engine, which is still in working order. Installed in 1934, the six-cylinder engine was the most powerful marine diesel in the Pacific Northwest at the time. |

One of the 50 was John Nordstrom, founder of the luxury clothing and fashion accessories store chain based in Seattle.

After striking it rich, Nordstrom decided to sell his claim rather than work it himself. Once he paid off his debts, he had $13,000 left over that he used to start a shoe store that ultimately grew into the Nordstrom chain.

Arthur Foss provides a way for the public to connect with these events that have helped to shape the world we live in, said Ashwell, who is a historical archaeologist by training.

The Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park sometimes works in cooperation with Northwest Seaport by sending a park ranger to Arthur Foss to explain to visitors the connection of the boat to the region’s history.

“It’s a tangible connection to a fairly significant event, not in American history but in global history,” Ashwell said.

“It really captured the world’s attention,” she said, noting that the gold rush attracted prospectors from as far as Japan, Egypt, New Zealand and South Africa. “People from all over the globe were affected by the event.”

The tug has special significance for Foss, of course. In 1929, Foss Launch & Tug Co. bought the boat (which was already 40 years old) for $1,000, plus $3,500 in towing services. The company named it after one of the three sons of the founders of the company, Andrew and Thea Foss. And by an odd coincidence, both the company and the boat will be marking their 125th anniversary during 2014.

Mike Skalley is a Foss employee who is acutely aware of the importance of Arthur Foss. While his official title is manager of the billing department, he also serves as the company’s unofficial historian.

Foss plans to hold an open house this summer to mark the company’s 125 years in business. And Skalley hopes the event will take place near where Arthur Foss is moored, reminding people of how the history of the company and the tug intersect.

As a nautical historian, Skalley wants to see Arthur Foss preserved. The tug is “the oldest floating vessel on the West Coast,” he said. “You would hate to lose something like that.”

And he would love to see it put back into operating condition. “We have a real treasure here,” he said. “We want it to be an active part of Puget Sound history.”

But he also understands the hurdles. The condition of the boat has deteriorated since the 1980s, when it took its last voyages. “They’ve got a long way to go” to get it back into operating condition, he said.

There’s dry rot in the hull and bulwarks, he observed, while the mechanical systems aren’t in bad shape.

“From the machinery point of view, it’s in pretty good shape. It’s the wood” that poses the worst problems, he said. “Maintaining tugs of that nature, that’s a huge undertaking.”

Loggers is of course aware of the magnitude of the task facing the museum. But he is convinced Arthur Foss will once again voyage around Puget Sound, and perhaps even head north to Alaska.

“This is not a static museum,” he said. “She’s a living museum ship.”