Though the case has yet to even reach the courtroom, the investigation into the January sinking of the Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia is already raising eyebrows as everything from the captain’s actions to his morals are debated publicly. The accident is also raising questions about how the increasing amounts of navigational data available in the wake of incidents like these might change the way such cases are prosecuted — and even the way ships are run.

Since becoming mandatory for most commercial vessels in 2005, Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) have broadcast data mariners use to identify nearby vessels, both to improve communications and lessen the risk of collisions. But a new breed of vessel-tracking and fleet-management software collects that raw data and creates and accommodates a number of new uses for it.

Archival data can be used to reconstruct the events leading up to groundings, sinkings and collisions. But vessel owners can also use the data to closely monitor a ship’s progress in real time and contribute greater input into decisions made on the bridge.

|

|

|

|

|

Courtesy PortVision |

|

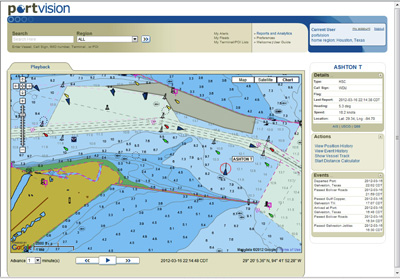

These images, spaced a minute apart, show the offshore support vessel Ashton T as it approached and then grounded on the north jetty in Galveston, Texas, on March 12. Data displayed include time, heading, speed and position. |

“I’m sure that feeling of being an independent decision maker has changed for masters,” said Capt. George Sandberg, a retired mariner and instructor at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point. “People feel someone looking over their shoulder — that’s not necessarily a bad thing, if it leads to accountability.”

With so much data now accessible, what are the implications it may have on how the liability of owners and captains is determined? How will it change the independence of ships’ masters? The Costa Concordia sinking may offer a glimpse into the future for the maritime industry.

A number of systems currently on the market collect and store ships’ AIS and other data using ground-based antennas. Subscribers can access the data from any computer terminal with an Internet connection. Some systems, like AIRSIS’s PortVision, also collect data using satellite antennas to provide coverage areas beyond major ports, including open ocean.

“We track ship events — when they departed, when they passed certain points, how long has it taken a vessel to do a transfer at a dock, all sorts of things,” said Jason Tieman, PortVision’s director of maritime solutions. The company stores more than 15 billion daily vessel track movements, and processes and analyzes more than 40 million vessel movements each day.

The vessel tracking service began as a way for oil refineries to know where tankers were at any given moment for scheduling purposes, since late or missed deliveries can cost millions of dollars in lost sales or insurance claims. “For example, say there was waterway blockage due to an oil spill. Because we have all the data on all the vessels that were in the area, when all the claims start to come in a few years after the incident, a replay shows exactly what vessels were affected by the incident and that lost business because of it,” Tieman said.

Data is archived for five years at 30-second intervals, and can be accessed to “replay” a ship’s route for training exercises or legal purposes. It’s the latter use that is beginning to change the way maritime incidents are investigated and claims are settled.

“In court, it’s hard to argue against this data when it’s from the same GPS from your vessel that you’re supposed to be navigating with,” Tieman said.

More than 30 people died in the Costa Concordia sinking. The captain, Francesco Schettino, is under arrest on suspicion of manslaughter, and the ship’s owner said he made an “unapproved, unauthorized” deviation in course when he sailed too close to Giglio Island, off the west coast of Italy. There was no navigational reason to be anywhere near the rocks, and officials have said it appears Schettino deliberately steered alongside the island to perform a salute, or “take a bow.”

The 4,000-passenger cruise ship hit a rocky outcrop, took on water and began to list. Positioning data shows that Schettino tried to turn back toward port, shifting the water in the bilge and causing the ship to list severely starboard.

Dutch-based Quality Positioning Services (QPS) released a reconstruction of the incident using data collected from a network of ground-based receivers and streamed into its Qastor Pilotage software. Using satellite imaging and a computer image of the cruise ship, QPS created a three-dimensional model showing the vessel’s route and navigation information in the minutes before and after the incident.

QPS has not taken a public stand on whether or not the incident could have been avoided, and did not return calls for this story.

Positioning data show that Costa Concordia did deviate from its planned course to sail closer to the island — and that it had followed a similar route last summer. It also revealed that it is the only cruise ship over 3,000 gross tons to pass anywhere near that close to the island.

Vincent Foley, an attorney with admiralty law firm Holland & Knight — and a former mariner who graduated from Kings Point — said that, generally speaking, the admissibility of computer data as evidence in such cases is not something to be taken for granted.

“Computer reconstructions of events, like casualties and disasters, have been rejected in several circumstances,” he said. “When it’s supported by AIS information or other data, then you can shore it up and say that the basic geographic info is reliable to within a certain number of feet, and that gives the court the level of accuracy and reliability of the data. You’ll still need to satisfy the court that there was not some manipulation of that AIS data in creating that reconstruction. It’s going to be tested, and there have been several incidents of models being rejected as junk science, or not meeting scientific requirements.”

Foley said the better the information is, the more likely that a judge would accept it as meeting the scientific reliability factor, and having an expert witness who can explain the data to the court can help.

Data can also be used to contradict eyewitness testimony, which is not necessarily accurate. “The data can then be used for cross-examination, or to keep witnesses honest — witnesses will testify in a lot of cases in favor of their own accountability,” he said. “People will manipulate evidence in their favor.”

Whether that data comes to bear in the Costa Concordia trial has yet to be seen, but Clay Maitland, Connecticut-based managing partner of International Registries Inc., said the impact of the incident on how ships operate may last long after the trial is over.

“The ship went where it shouldn’t have been,” Maitland said. “The claim will be made that the ship wouldn’t have been there if the management ashore had monitored it better.” That kind of monitoring may lead to the “declining independence of the ship’s master and mates,” he said.

Sandberg said there may be a darker side to the practice of shipowners monitoring vessels in real time. If they can second-guess masters’ every decision, they can undermine a captain’s confidence and independence, he said.

“However, the data is presented on a flat screen, that’s not the same as looking out the window on a bridge,” he said. “People looking at this data have to have the experience to know what it’s telling them. Even if the data is correct, it’s still easy to make wrong assumptions.”

He compared the current state of technological development to the 1980s, when satellite communications removed some of the isolation from bridges. Until that point, there was limited ship-to-shore communication between ports, and ships’ masters made decisions with more independence. “Beginning in the ’80s, there would be constant communication with shore,” he said. “You’d get a knot in your stomach when the telex clicked on, because you’d know it was the home office.”

When used proactively, all that available data can be beneficial, Sandberg said. A few years ago, he worked with a company whose ship was involved in a low-speed collision with a barge. Because there was no visible damage, the captain never reported the incident, and the owners didn’t learn about it until the barge’s insurance company filed a claim using ECDIS data to document the collision.

The company used the incident as an example for instruction rather than simply dismissing the captain.

“That was a great way to handle it,” he said. “Using it for training was smart. There are real benefits to be had there.”