Just after midnight, as the pilot boat pounded through waves generated by 20-knot winds sweeping up Chesapeake Bay, the dark outline of the huge containership became visible through the spray.

This was Mediterranean Shipping Co.’s Rania, a 1,090-foot-long, 142-foot-wide containership on its way up the bay from Norfolk, Va., to Baltimore.

As a post-Panamax vessel, Rania represents the dawn of a new era for U.S. ports on the East and Gulf coasts. Until recently, none of those ports could handle a ship like Rania. They didn’t have cranes big enough to reach all the way across a ship this wide. Or they didn’t have channels deep enough to admit a ship drawing close to 50 feet. Or bridges over the approaches were too low to permit such a vessel to pass safely underneath.

|

|

Will Van Dorp |

|

The ports of New York and New Jersey are spending over $1 billion to raise the Bayonne Bridge. |

All this is changing as a result of the reconfiguration of the Panama Canal. Since the canal opened in 1914, its locks have restricted the size of ships that could fit through — the biggest would be 970 feet in length with a beam of 106 feet and a draft of just over 41 feet. The Panama Canal Authority is in the midst of a $5 billion-plus project to build a new set of locks that will permit the passage of much larger vessels. The new locks, expected to open in 2015, will be 1,400 feet long and 180 feet wide and have a water depth of 60 feet.

That means that many vessels that now unload their cargoes at West Coast ports for transshipment to Eastern markets by rail will have an all-water-route option to the East. Ports like Baltimore, Norfolk, New York, Savannah, Charleston, Miami and New Orleans are all preparing for what they hope will be a bonanza of Far East cargo carried by post-Panamax vessels.

The pilot boat approaching Rania belongs to the Association of Maryland Pilots. Venturing out onto the Chesapeake from the pilots’ mid-bay station, the boat was taking me and my guide, Capt. Eric A. Nielsen, president of the pilots’ group, to observe how the Port of Baltimore is getting ready to handle this new generation of large containerships.

As we approached the northbound ship from the port side at a point about 60 miles south of Baltimore, Rania turned slightly to starboard to create a relatively calm patch of water in the ship’s lee. Once up the short ladder leading to a hatch in the hull, we were accompanied to the bridge. There I was introduced to Capt. Nick Watts, the Maryland pilot who was guiding the ship on the 150-mile transit from Norfolk to Baltimore.

Piloting very large vessels is not a new experience for Watts or the other Maryland pilots. Baltimore has long been an important coal port. During the late 1980s, the system of dredged channels leading to the port was deepened to 50 feet to accommodate the big bulk carriers that were becoming common at that time.

Watts, who became a senior pilot with an unlimited license in early 2013 and has been with the Maryland pilots for six years, noted that a big containership like Rania handles very differently than a big collier. “This ship can do up to 20 knots,” he observed. “It handles a lot better than a bulk carrier.”

Rania can draw as much as 49 feet, but on this transit of the bay its draft was 39.6 feet, well short of the 47.5 feet that is the maximum the pilots will permit in the channel system. The ship was now about 30 miles south of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge (actually two parallel suspension bridges) spanning the bay just east of Annapolis. This section of the bay has naturally deep water, so ships are not confined to a narrow channel.

“We’re on autopilot now,” Watts said. “We use hand steering whenever we’re in the channel.”

|

|

John Gormley |

|

Maryland pilot Capt. Mark Fithian guides Rania into the deep-draft berth built to accommodate post-Panamax ships in Baltimore. |

Nielsen explained that the naturally deep water here ranged from a half mile to three-quarters of a mile in width. In this section the water was generally over 60 feet deep and in places well over 100 feet. The faster a ship goes, the greater the squat effect, which would make the stern sit lower in the water. In this deep water that was not a concern, as the ship headed north at its full maneuvering speed of about 17 knots.

Still the dredged sections of the route do create special conditions that complicate bringing a big ship into Baltimore, particularly in the northern part of the route that Rania was now approaching. Above the Bay Bridge there are 17 miles of dredged channel leading to Baltimore. While the main channels south of the bridge are at least 800 feet wide (they are 1,000 feet wide near the mouth of the bay), north of the bridge they are 700 feet wide with multiple turns.

The pilots are fortunate to have naturally deep water in between the dredged channels, Nielsen said.

“If an ore ship is meeting a big containership, one of them will slow down and let the other one clear the channel so it seems seamless,” he explained. “We avoid meeting in bends. … We have bends and straightaways. We meet at the straightaways.”

Above the bridge, even greater caution is required. Nielsen noted that the water outside the channels is generally shallower there than in the sections farther south. “The hydrodynamics are exaggerated in the shallows above the Bay Bridge,” Nielsen noted.

|

|

John Gormley |

| The ship, which has a capacity of 8,402 20-foot containers, approaches the dock at Seagirt Marine Terminal. |

Although the naturally deep water continued right up to the bridge, Watts began to reduce speed as he approached because of the presence of construction barges there. “As we go through the Bay Bridge, we’ll slow down so we won’t throw too much of a wake,” he said.

He also asked the master, Capt. Danilo Popivoda, to have a member of the crew stand by the anchors so they could be deployed in an emergency.

Ships coming to Baltimore from the south have to pass under three spans to reach the docks — the two of the Bay Bridge and then the Francis Scott Key Bridge at the entrance to the harbor. The air draft of the Bay Bridge is listed as 182 feet and the Key Bridge is listed as 185 feet. That means the biggest ships in the MSC fleet will be able to pass safely underneath.

One complication is that suspension bridges can sag a bit under heavy loads in hot weather. “I’ve never seen it lower than 185 feet,” Nielsen said of the Bay Bridge. The tallest ship that Nielsen has seen come to Baltimore had a height of 178 feet above the water.

If the day ever comes that the bridge does sag temporarily to a height of less than 182 feet, there will be ample warning and the pilots will be able to operate accordingly.

The Bay Bridge has “a real-time air draft gauge system courtesy of NOAA,” Nielsen said.

When it comes to bridge heights not all ports are as fortunate as Baltimore. In the race to prepare for the opening of the new Panama Canal locks, one of the biggest hurdles facing the ports of New York and New Jersey is the Bayonne Bridge, which crosses the Kill van Kull, the principal route for accessing the ports’ major container terminals. The Port Authority of New York & New Jersey has decided to spend in excess of $1 billion to raise the air draft of the bridge to 215 feet, up from the current height of 151 feet.

|

|

John Gormley |

|

Capt. Danilo Popivoda, master of the 1,090-foot Rania, which has a beam of 142 feet, 36 feet wider than a Panamax ship. |

Norfolk, like Baltimore, is a major coal port that has long had 50-foot channels to accommodate bulk carriers. New York is expected to have 50 feet of water soon. Charleston, Savannah, Miami and New Orleans also hope to be able to compete for the larger ships by deepening their channels.

North of the bridge, the opportunity arose for me to witness Watts working out a passing arrangement with a tug and barge while the vessels were operating within a channel. Over the radio, the tug captain told Watts he would try to stay close to the edge of the channel.

“Do you want me to slow down?” the tug captain asked Watts.

“No, I’d rather come by you in the straightaway,” Watts replied.

At a little after 0330, Rania had caught up with the tug and barge. With the ship moving at 12.8 knots, Watts ordered slow ahead. A few minutes later he ordered dead slow as the speed dropped to 9.4 knots. After Watts had ordered hard starboard, Nielsen observed, “The ship handles a little more sluggishly at slow speed.”

As the ship came even with the tug, Watts ordered slow ahead to pick up a bit of speed as the ship overtook the tug, followed by half ahead. Within a few minutes the ship was back up over 10 knots and approaching the Key Bridge. Here the ship rendezvoused with two Moran tugs, Annabelle Dorothy Moran and Mark Moran. A pilot boat also came alongside to deliver a docking pilot and take Watts off the ship.

The docking pilot, Capt. Mark Fithian, is also a member of the Maryland pilots. At 0439, he relieved Watts, who had been conning the ship for about 10 hours. “It’s a fatigue issue,” Nielsen said.

After passing under the bridge, the ship would have to make a hard turn to starboard to enter the side channel leading to Seagirt Marine Terminal, where the ship was to dock. The terminal has a new deep-draft berth (completed in 2012) served by four new container cranes designed expressly to load and unload post-Panamax ships. The cranes, costing $10 million each, became operational in January 2013.

|

|

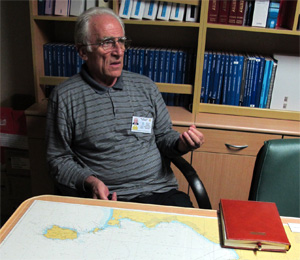

John Gormley |

|

Capt. Eric A. Nielsen, president of the Association of Maryland Pilots. His group has played a leading role in demonstrating Baltimore’s ability to handle big ships safely. |

Both Moran tugs are rated at 60 tons of bollard pull and Rania is equipped with a 4,000-hp bow thruster. But with the wind blowing at 20-plus knots out of the south, this would be a tricky maneuver. One of the tugs, assisted by the bow thruster, would be pushing on the port bow, while the other tug would be pushing from the starboard quarter. Together they would help the ship make almost a 90° turn.

To ensure that post-Panamax ships could be brought in safely to Baltimore, the Maryland pilots went to the nearby Maritime Institute of Technology & Graduate Studies (MITAGS) to conduct simulations. Conducted in the spring of 2012, the simulations modeled the characteristics of an MSC vessel even larger than Rania — MSC Kalina, a 14,000-TEU vessel with a length of 1,200 feet and a beam of 168 feet.

The idea was to see what would happen if the pilots tried to bring such a large post-Panamax ship into Seagirt in a variety of conditions. “We would see how the ship did, see if they made it,” Nielsen said.

One of the things they found is that in 30-knot winds, a ship of that size would need a bow thruster and three tractor tugs with bollard pull of 60 tons. They also concluded that some dredging would have to be done to moderate the angles in the access channel that leads to the terminal. That dredging work is to be done during 2014.

Even though the pilots have experience handling large ore ships and LNG carriers, containerships pose a special challenge because of the large surface they present to the wind. “It’s the mountain of containers that is the difference,” Nielsen said.

The problem facing Fithian as he brought Rania to the dock would be a real-world test, not a simulation. After getting the ship around the tight turn in high winds, he would have to turn the ship again, this time to port, to bring it parallel to the terminal with the full force of the wind blowing against the ship and pushing it toward the dock.

Fithian repositioned the tugs along the port side and had them pull against the ship with their hawsers to resist the force of the winds, as the ship slid slowly toward the terminal and then came to rest gently against the dock.

After the ship was safely secured at 0525, Fithian estimated that the winds had been blowing at up to 25 knots. “I would not have wanted to do it in more,” he said.

While Fithian was working the ship slowly to the dock, the ship’s master, Capt. Popivoda, watched from the starboard bridge wing. He apparently liked what he saw. Once Fithian’s work was done, he turned to me and said, “This pilot is an artist.”

Capt. John Traut was one of the Maryland pilots who participated in the simulation exercises at MITAGS. An experienced docking pilot himself, he acknowledges the challenges of handling very large containerships, but he is confident Baltimore has the resources and skilled people to do it successfully.

“Baltimore is a good port with a tight-knit community,” he said. “Everybody is interested in making this work.”

“I think the port has huge potential with the infrastructure in place and envisioned,” he continued. “We want to be efficient, safe. We want everybody to have a good experience in this port of call and to come back and visit us again.”