A ship anchored five miles southwest of Montauk Point Light on Long Island for several weeks last August had an unusual profile — a large boxy deckhouse far aft and high bow with significant open deck space in between. M/V Ocearch, measuring 126 by 32 feet, may be the only repurposed Bering Sea crabber off the East Coast of the United States. On deck, a crane and a starboard-mounted lift platform present a unique configuration of machinery. And the Park City, Utah, port of registry painted on its stern adds another intriguing detail. Aboard the vessel, stickers and patches display a plethora of logos — Costa, Caterpillar, Yeti, SAFE, Contender, DYT Yacht Transport, Yamaha, Landry’s and more — giving the hint of a NASCAR racer.

|

|

The vessel, measuring 126 by 32 feet, has a spacious forward deck to accommodate researchers and their subjects. |

But it’s the mission of M/V Ocearch and its crew that distinguishes it from any other vessel afloat. Ocearch, the name of both the ship and the funding and advocacy organization, studies live sharks — focusing on arguably the ocean’s top predator, the great white. Ocearch founder Chris Fischer points out that although dead sharks provide lots of information, his project gives scientists an opportunity to learn from live specimens. To do this, Ocearch catches a shark, measures it, takes samples of tissue and various body fluids, removes parasites, attaches tracking devices and then releases it back into its habitat — all in less than 15 minutes. The key is the lift platform, approximately 20 by 25 feet and capable of raising at least 35 tons. The largest great white sharks caught have weighed less than 3 tons.

|

|

Shark tags can be sub-dermal, mounted on the fin, or attached elsewhere on the skin and pulled through the water. |

According to Tobey Curtis, a shark and fishery policy analyst at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the lift is a superior platform for tagging and sampling large sharks that would be otherwise very difficult to handle over the side of a smaller boat. “With these large fish raised out of the water, they can be handled relatively safely and quickly while researchers attach multiple tags and collect numerous biological samples as efficiently as possible,” he said. Different types of tags can collect and transmit vital information about the shark for up to five years.

M/V Ocearch, built by Horton Boats of Bayou La Batre, Ala., in 1990 as Arctic Eagle, left the crabbing fleet in 2005 through a federal buyout program designed to reduce the fleet size by 10 percent. The first buyer converted it to a yacht/mothership and added the hydraulic lift to move his 45-foot fishing boat between the deck and the water. Fischer, then host of ESPN’s award-winning “Offshore Adventures” TV show, bought the mothership and fishing boat in 2007. At that time, Fischer’s project of catching fish and selling television was not focused on sharks but rather on billfish.

|

|

Crewmembers D.J. Lettieri and Danny Caporaletti set up camera equipment on M/V Ocearch’s lift platform. The 20-by-25-foot lift can hoist up to 35 tons. |

“I was trying to finish what Zane Grey began with billfish. But fisheries experts always wanted to talk about the shark crisis, the sense that sharks — the apex predator of the oceans — were threatened by uncontrolled fishing for their fins,” Fischer said. “Sharks are the balance keepers, lions of the oceans, but some 200 million are killed for soup each year, an unsustainable number. We should be worried what will happen to the oceans and to us if the balance keepers are wiped out.”

These conversations and concerns led Fischer to create his model, which he described as “bringing professional mariners and fishermen together with academics to study live animals in a collaborative, open-source, ocean-first way.” Shark scientists had studied and harpoon-tagged live sharks prior to the Ocearch project, but large information gaps persisted concerning where sharks bred, “raised” their young and more. “Fishermen had access and knew more, or differently, than the academics, but you can’t create policy on a fisherman’s story, and we need the right policies to ensure the sharks’ survival and the ocean’s health,” he said.

|

|

Troy Dionne operates the SAFE 21, which shuttles personnel and supplies between ship and shore. |

As of early October, Ocearch had completed 27 expeditions, having partnered with 131 researchers from 59 regional and international institutions in nearly a dozen countries. With limited bunks, only a handful of scientists might rotate in during an expedition, but they gather data for other researchers’ projects as well as their own. Curtis believes that the open-source policy has accelerated understanding of the movement patterns of the sharks Ocearch has tagged. “The online Global Shark Tracker allows scientists, fisheries managers, students and the interested public to learn alongside each other, expanding the science as well as engaging and educating the public about shark biology and conservation,” Curtis said. Global Shark Tracker displays real-time information about the tagged sharks, much as the automatic identification system (AIS) does for shipping.

|

|

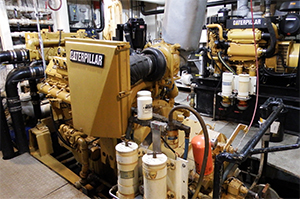

Propulsion on M/V Ocearch is provided by a pair of Caterpillar 3412 main engines that were installed in 2011. |

Ocearch’s expeditions are funded by what Fischer calls “socially responsible companies,” whose logos are prominently placed on the ship and the garments of the crew. In 2011, Caterpillar repowered M/V Ocearch with two Cat 3412 propulsion engines and C4.4 and C6.6 generator sets. Other major sponsors include DYT Yacht Transport, which several times has used its heavy-lift ship to reposition M/V Ocearch across oceans. Costa, a maker of sunglasses, provides funding and gets recognized not only with stickers but also in nomenclature: An immature 12-foot female white shark weighing just under 1,700 pounds was recently named Miss Costa after being caught and tagged off Nantucket. The Global Shark Tracker shows that in the following two weeks, Miss Costa swam from waters off Nantucket to Nags Head, N.C.

|

|

The starboard-mounted helm affords a clear view of deck areas. |

M/V Ocearch is registered as a recreational vessel serving as a floating science lab. Fischer considers its mission game-changing in the tradition of Jacques Cousteau, whom he frequently mentions. “We are learning what has never been learned at rates never attained, and we’ve leveraged that to change the way academic research on sharks has been done,” Fischer said.

M/V Ocearch and its crew — on board and ashore — make up a truly unprecedented team that may enhance future ocean conservation policies.