The rush to lay keels before EPA Tier 4 emissions rules took effect contributed to a surge of new construction in recent years. Those better days in some ways contributed to the current slowdown in building that’s been compounded by economic headwinds.

Many in the marine industry saw the change coming. Around this time last year, shipyard managers with a yearlong backlog expressed concern about the lack of new work in the pipeline. Suppliers also noticed an impending dropoff.

“I made the comment last year that we had a backlog until the middle of this year and then it looked like it was slowing down. My predictions were true,” said Brandon Durar, president of JonRie InterTech, maker of winches and deck gear. “We are still building rapidly, but there is not much backlog left.”

There are no firm numbers for vessel deliveries in a given year, but the website Shipbuildinghistory.com is one comprehensive source. The site, compiled by Tim Colton, shows 122 tug and towboat deliveries in 2015 and 110 in 2016. For the six years between 2010 and 2016, the average was about 108 new tug and towboats a year.

The start of 2017 has been noticeably slower. Through May 1, 27 tug and towboats have been delivered. Plenty more vessels will be completed later this year, but the total number could fall below 100.

Well-documented trends led to the recent surge in new construction, and in many ways foreshadowed the current challenges. In particular, tug and towboat operators pushed ahead with ambitious Tier 3 projects ahead of the Tier 4 cutoff, which has since come and gone. Shipyards on all three coasts are still working through backlogs caused by this surge in orders, but most will be finished by 2018.

Despite some early adopters, orders for boats that meet Tier 4 emissions standards have been slow to materialize. Meanwhile, the steep drop in offshore support vessel (OSV) construction and other oil field vessels also has more shipyards bidding for tug projects.

|

|

A welder working on Rosemary McAllister, the second of three Tier 4 tugs under construction at Horizon Shipbuilding. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

“Oil prices are still down, which is really depressing the oil patch down south, which is increasing the competition for the tugs,” said Bruce Washburn, naval architect and executive vice president with Washburn & Doughty shipyard in East Boothbay, Maine. “Companies that normally wouldn’t bother with a little thing like that now figure it’s better than nothing.”

“We are facing a lot stiffer competition and hungrier competition for what work is out there,” he continued. “That, plus there are a lot of companies that really pushed as many Tier 3 boats as they could, so that probably extended into what their normal build rate was going to be.”

Tug operators that might normally build two or three vessels as part of a fleet replacement plan, for instance, might have ordered twice that many boats ahead of Tier 4. Washburn suggested these same operators are now slowing down to “catch their breath.”

Travis Short, president of Horizon Shipbuilding of Bayou La Batre, Ala., acknowledged similar trends during a March interview. Although his yard has typically operated with a backlog of 24 months of more, it is less these days. What new work is out there requires aggressive bidding.

“When a market gets into a slump, it turns from a builders’ market to a buyers’ market and all of a sudden you’re doing work at margins that are less than satisfactory,” he said, adding that the current period is definitely a buyers’ market.

Demand for bluewater tugs has remained relatively steady and likely will remain so in the coming year. But brownwater construction, Short said, is in “a little bit of a slump.” He doesn’t expect a turnaround for at least another year.

The slowdown in the oil patch has reverberated across the maritime industry. Huge numbers of OSVs are stacked up in the Gulf, meaning demand for new oil field vessels and tugs likely won’t rebound for some time. Meanwhile, companies that move oil or support the petroleum industry also are feeling the pinch, potentially crimping demand for new vessels.

|

|

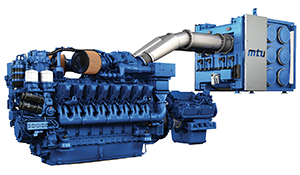

MTU’s first Tier 4 engines will be delivered later this year. |

|

MTU |

“It’s a little slower due to the slowdown of the oil production in Alaska,” said Capt. Russell Shrewsbury, vice president of Seattle-based Western Towboat, which hauls cargo barges and rail cars to Alaska. “A lot of western Alaska freight volumes dropped off dramatically.”

Western Towboat is still building new boats, but the company is hoping for a quick rebound in the Alaska trade.

The Damen-designed tugboats that Edison Chouest Offshore is building for tanker escort and response work around Prince William Sound, Alaska, are one big exception to the oil slowdown. Chouest is building the vessels at its own shipyards.

Despite the slowdown, there are reasons for tempered optimism. The new Panama Canal locks are facilitating bigger ship calls at East Coast ports, although perhaps initially not in the numbers some expected. If this picks up, more operators could be in the market for new tugs, according to Robert Allan, chairman of Robert Allan Ltd. in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Durar, of JonRie, predicts regulatory changes, particularly the Coast Guard’s Subchapter M, could force towing companies to replace aging boats. “I don’t believe some of the older tugs will meet the requirement for Subchapter M,” he said. “That should be the next trend for replacements.”

That is already happening in at least one notable case. Great Lakes Towing Co. is building 10 new vessels at its Cleveland shipyard. These tugs will replace aging tugs in its Great Lakes fleet, reducing the need for future repairs and upgrades. The lead boat, Cleveland, is profiled here.

Completion of high-profile Tier 4 boats, in particular Earl W. Redd, Capt. Brian A. McAllister and Caden Foss, also could demystify Tier 4 engine technology and aftertreatment systems. Caterpillar, for instance, has installed a telematic system that will gather real-world data from engines installed on Earl W. Redd.

|

|

Master Marine yard manager Jody Krause aboard the Marquette Transportation towboat St. Matthias. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

This information will allow Cat to compare its modeling and lab testing with actual results. Cat predicts fuel savings of 5 to 10 percent with its Tier 4 engines compared with identical Tier 3 mains, and GE is predicting similar gains. These improvements largely come from changes to engine timing, which resemble Tier 2 calibrations.

Jason Spear, Cat’s marine product definition engineer, expects the company’s predictions will hold up. “I would not anticipate a whole lot of difference from what we calculated compared to (what happens) in the real world,” he said.

There are also signs that inland operators are looking to build. Ed Shearer, principal naval architect with The Shearer Group in Houston, said the firm is developing Tier 4 towboat designs for potential customers. Other operators are exploring triple-screw tugboats with roughly 800-hp engines, which are small enough to fall under Tier 4 rules.

“We are also looking at diesel-electric systems utilizing several smaller engines which, when combined, give substantial horsepower through two propulsion systems,” Shearer said.

Legislation under consideration in Washington also could jump-start some lagging sectors of the marine industry. The Trump administration’s proposed tax and regulatory overhauls could reduce business costs, while a rise in infrastructure spending could spur demand for construction materials that move over water. Revised trade pacts could affect farm exports.

“So far, we haven’t noticed any substantial benefits from the Trump administration for our industry, but there is a lot of optimism and positive thinking,” said Randy Orr, president of Master Marine in Bayou La Batre, Ala.

Whether the new administration achieves these goals is anyone’s guess. And even then, there will likely be a lag between rising demand and the need for new vessels.

|

|

The 13,000-TEU COSCO Development arriving at The Port of Virginia in May. Bigger ships moving through the Panama Canal could spur demand for more powerful tugs. |

|

The Port of Virginia |

“It really varies as to the segments and the various niche markets,” said Bob Beegle, president of Coupeville, Wash., tug and towboat broker Marcon, “but in general there is too much equipment out there chasing too little work.”

A plateau on tug hp?

Horsepower and bollard pull have steadily crept up on docking and escort tugs, especially in the past 20 years. Some now believe performance will begin to plateau around 80 metric tons of bollard pull.

“I can’t see it getting much higher, in part because the tugs are pushing on the sides of ships and we are reaching the thresholds of contact pressure limits in many instances,” said Allan, of RAL.

There also are practical reasons for the pushback, so to speak. For one, most new ship-docking tugboats have z-drives, allowing captains to position the tug quicker and more accurately. This allows more consistent application of force, rather than fewer shorter bursts of power.

“Your average ship-docking dock today is somewhere around a $10 million investment, and certainly more if you are building in North America,” Allan said. “They are not insignificant investments, so the owners are being quite judicious.”

Indeed, there are also financial concerns: Larger engines cost more and require larger, more expensive components. Practically speaking, tugboats also use maximum power only a small percentage of the time, meaning there is little incentive to “overpower” a vessel.

Newbuilds offer maximum versatility

The first three Tier 4 tractor tugs to hit the market, Earl W. Redd, Capt. Brian A. McAllister and Caden Foss, are brawny, powerful vessels ready to handle very large ships. But all three also are outfitted with towing winches for maximum versatility.

|

|

Nichols Brothers Boat Builders of Freeland, Wash., outfitting the 120-foot Mount Baker this spring for Kirby Offshore Marine. |

|

Alan Haig-Brown |

This is not groundbreaking — Western Towing’s Titan-class tugs have long been used for ocean towing, ship docking and barge handling. But the trend does seem to be catching on, according to Johan Sperling, vice president of Jensen Maritime Consultants.

“The stereotypical harbor assist/escort tug looks different today than it did five years ago because (operators) are needing to make it more diverse in the things it can do,” he said in a recent interview. “If you look at some of the newer designs today, they are becoming multipurpose vessels.”

Design-wise, that often translates into raised forecastles and more powerful engines to handle rougher seas outside the harbor. Oversized fuel tanks also allow these vessels to take rescue towing jobs far offshore, or pursue long-haul ocean towing work.

More z-drives on inland waterways

It’s been nine years since Southern Towing began the modern z-drive towboat era with its vessels David Stegbauer and Frank T. Stegbauer. Most towboats built today still have conventional propulsion, but z-drives are becoming more common on inland waterways.

Over the past two years, Paducah, Ky.-based Marquette Transportation has taken delivery of 11 2,000-hp z-drive towboats from Master Marine. The last of the series, St. Matthias, was completed in late 2016. American Commercial Barge Line of Jeffersonville, Ind., has added new z-drive towboats, including the 2,000-hp American Strong built by JeffBoat and American Valor built by Steiner Shipyard.

Shearer, of The Shearer Group, said efficiency gains have led to wider acceptance. In one example, z-drive towboats running from New Orleans to Cincinnati burned 10 percent less fuel and took a day less to make the round trip than towboats with conventional propulsion.

“We looked back at what we predicted versus what happened, and (z-drive boats) beat our estimates for fuel efficiency and trip times,” he said. “A lot of it is due to propeller efficiency.”

|

|

VT Halter Marine built Bouchard Transportation Co.’s 6,000-hp ATB tugboat Frederick E. Bouchard, which entered service last summer. |

|

Bouchard Transportation |

SCF Marine of St. Louis is taking z-drive propulsion a step further with SCF Vision (more detail here). The 6,600-hp vessel delivered earlier this year is the largest and most powerful ASD towboat in the U.S., and two sister vessels are planned.

Autonomous tugs on the horizon?

The same technology that propels driverless vehicles could one day appear in tugboats — in fact, it seems like more a question of when than if.

Allan said autonomous tugs are not yet at a similar development stage as driverless cars, but they are not that far behind, either. His Vancouver, B.C., firm is working on concept plans for remotely operated tugboats. It does not yet have a buyer, but Allan said operators around the world are showing interest.

“We feel we have all the technical aspects of autonomous tugs dealt with, but the biggest challenge will be dealing with it from a regulatory and probably a union operations perspective,” he said.

Right now, these tugs would still require humans at the controls, although the operators would probably not be on board. In a two-tugboat escort or docking maneuver, for instance, Allan suggested one tugboat would be fully manned, and a second master on the manned tug would be in control of the autonomous vessel.