Capt. Michael Schlechter stood at the port bridge wing control station of the fast ferry Fairweather as the 19,320-hp catamaran prepared to leave the dock just north of Juneau, Alaska, for a four-and-a-half-hour, 132-nm voyage to Sitka.

“All set, chief?” Schlechter asked chief mate Brian McCarthy, who replied, “Clutching in all four.”

Using the ferry’s four Kamewa 90S11 series waterjets, the captain maneuvered the 235-foot Fairweather away from the dock, while McCarthy kept an eye out for hazards ahead. “You have this one guy cutting across,” McCarthy warned Schlechter.

Just moments into the voyage, the bridge crew was already exhibiting the high degree of cooperation and vigilance that mark Fairweather’s operations.

Any capable bridge crew must exhibit those traits. However, aboard Fairweather, they are of special importance, first of all because of its speed. Capable of reaching over 43 knots, the ferry travels along much of the route at 35 knots.

|

|

Capt. Michael Schlechter (left), at the starboard controls, docks at Sitka as second mate Joseph Krzesni assists. |

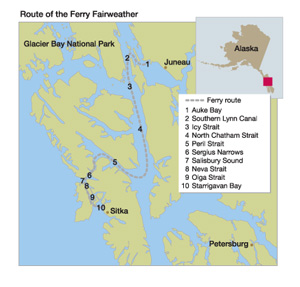

Plus there is the complexity of the route. While the first part of the voyage includes the transit of the wide Northern Chatham Strait, Fairweather then enters the aptly named Peril Strait, a twisting and narrow waterway with tidal currents that can reach as much as 8 knots in one section. The route finishes with two relatively straight but narrow waterways, the Neva and Olga straits.

Then there is the rapidly changing and sometimes severe weather. Because Southeast Alaska’s Inside Passage and connecting waterways are sheltered, heavy seas are not a common problem. But high winds, dense fog and persistent rain are.

Finally, there is the high volume of vessel traffic: the tugs and barges carrying the goods needed by the island and coastal communities of Southeast Alaska, which have no road links to the outside world; commercial fishing vessels exploiting one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth; charter boats and recreational boats pursuing the same fish, and cruise ships carrying tourists eager to witness this dramatic landscape and abundant wildlife.

On this voyage of Fairweather in early June, 92 passengers and 26 vehicles were aboard (the boat can carry up to 250 passengers, plus 35 cars).

As Fairweather headed south down the Northern Chatham Strait, there were five crewmembers on the bridge: three deck officers, an engineer and an AB.

At the dual main navigation stations, McCarthy, in the starboard seat, had the conn. Assisting him from the port seat was second mate Joseph Krzesni while the captain looked on. Off to their left stood AB Andrea Stevens, binoculars in hand. She served as lookout.

Fairweather has two engine rooms, one in each of the cat’s twin hulls, but the main control station for the vessel’s engineering systems is on the bridge. As Fairweather headed south, chief engineer Wayne Wilson monitored those systems from a center console located just aft of the navigation stations. He too had a pair of binoculars at his post.

|

The duties of AB Andrea Stevens include serving as a lookout on the bridge. She is seen here scanning the route ahead as the ferry transits Peril Strait. A holder of a 100-ton master’s license, she has been working on the ferry since it was delivered by Derecktor Shipyards in 2004. |

Because both the engineering and navigation functions are carried out on the bridge and because all five crewmembers present share responsibility for the vessel’s safe navigation, the bridge is known by another name aboard Fairweather. “It’s called the operating compartment,” Schlechter explained.

This arrangement places a premium on communication and coordination. Those are key elements in the safe operation of a vessel whose great speed allows little time to react to potential hazards.

“Right now we’re cruising at 35 knots,” said Wilson.

His primary role is monitoring the ship’s systems, including four new MTU 20V 4000 M73L engines, which were installed over the winter. (The first voyage with passengers following the repowering had taken place less than a month earlier, in mid-May.) He clearly embraces his non-engineering duties.

“I’ll act as a lookout. I have better side visibility than they do,” he said of the deck officers sitting up front.

Some of the hazards are of particular concern to him as the engineer. “Logs, that’s a big one for us,” he said.

The waterjets do not have grates, so any log that goes unseen has the potential to enter and jam one of them. To remove a log might require sending a diver down, but the loss of a single waterjet would not disable the ferry. “On three (waterjets) we can still maintain a service speed of over 30 knots,” he said.

In this part of the world, visibility is often less than optimal. Rain and fog are constant companions. And in the winter, the nights are long. To help the crew spot hazards, the boat is equipped with a night-vision camera that is sensitive to both low-level available light and infrared radiation.

Logs are not the only hazard. In these waters, whales are common and are a serious concern. “That’s another reason we’re all involved in looking out the window,” Wilson said.

Ice is particularly dangerous. Fairweather, like the other ferries in the Alaska Marine Highway System, is named after a glacier. The Fairweather Glacier is located in Glacier Bay National Park, about 60 miles northwest of Juneau.

“We did some runs all the way to Petersburg,” said Wilson. The route to Petersburg, about 175 miles south of Juneau, took the ferry past a couple of glaciers. “That’s what we were most concerned about, ice,” said Wilson. “The concern is definitely any ice touching an aluminum hull.”

|

|

First engineer Dennis Early at the engineering console on the bridge just aft of the posts occupied by the deck officers. Because the engineer and deck officers all have their work stations on the bridge, they prefer to call it the operating compartment. |

Stevens has been working aboard Fairweather since Derecktor Shipyards delivered the vessel to the state ferry system. “I’ve been on Fairweather since it came out 10 years ago,” she said.

Stevens may work as an AB, but she also holds a 100-ton master’s license. Her duties include working on the car deck. But after the ferry got underway, she reported to the bridge to serve as a lookout. “The main job is to keep a close and safe lookout for whales, drift, logs, people,” she said. “You avoid seaweed. It’s not the seaweed itself. It’s what else might be in there, a log.”

The ABs also make sécurité calls over the radio to warn other vessels of the ferry’s approach. Because of the many twists in the narrow waterways, vessels approaching each other are often out of one another’s sight. Delegating the sécurité calls to the AB reduces the possibility of distraction by the deck officers, thereby enhancing safety margins.

As Fairweather prepared to make a hard turn to starboard to exit the Northern Chatham Strait and enter the Peril Strait, Krzesni had the conn. A 2005 graduate of California Maritime Academy, Krzesni is the exception among the deck and engineering officers, who are mostly hawsepipers. As a cadet, he spent two months on another Alaska state ferry, Columbia, and was hired upon graduation to work on Fairweather.

He is appreciative of the integrated bridge. “It’s a lot more modern than the other ferries,” he said. “All the electronics are talking to each other. Sitting here I can see everything. It’s all right in front of you. It’s really nice.”

As the ferry approached Peril Strait still doing 35 knots, Stevens called out, “Whale off to starboard there.”

When the boat left Juneau, it had been cloudy, but now things were clearing up and a rainbow appeared above the mountains that define the strait.

Shortly thereafter — at 0923, about three hours into the voyage — the captain relieved McCarthy and took the right-hand seat. Krzesni continued to have the conn.

|

|

Virginia Howe illustration |

The trip down Northern Chatham had been essentially a straight shot down a wide waterway. In Peril Strait, the width would be measured in some places in feet rather than miles. In Sergius Narrows, at the far end of the strait, the width as delineated by the channel markers is only about 300 feet. The tidal currents there can reach 8 knots.

Schlechter, who has been master of Fairweather since its delivery a decade ago, appreciates the electronics, but is also conscious of their limitations. “Sometimes people rely too much on the technology,” he said.

He noted that Fairweather issues sécurité calls at set points along the route where oncoming vessels approaching a turn might not be able to see the fast ferry coming from around the bend. “Some operators, you give a sécurité call and they don’t answer you back,” he said.

Since Fairweather cannot assume that other vessels know the ferry is coming on quickly, the bridge crew has to stay alert, keep a sharp lookout, use the electronics without depending on them exclusively, communicate effectively and drive defensively.

Put another way, the principles of bridge resource management are rigorously applied and adapted to meet the challenges posed by a fast boat operating on a busy and complicated route.

Both the port and starboard conning positions have a complete set of electronic displays and engine controls. While one deck officer has the primary conning duties of steering and controlling speed, the other provides feedback and monitors the electronics. This arrangement allows for a high degree of cooperation and helps to ensure that the officer steering is not distracted by other responsibilities.

When the conn passes from one deck officer to the other, they do not change seats. So there is no distinction between the pilot and co-pilot seats, as in an airplane cockpit.

“We switch the conn every hour or so,” Schlechter explained.

At 0939, Schlechter took over the conn from Krzesni. This occurred just before the ferry entered the most demanding part of the route: the twists, turns and tides of Peril Strait. However, the change did not reflect Schlechter’s insistence on having the conn during the most challenging part of the voyage. The bridge officers routinely switch the conning sequence, so that all of them get regular turns at operating on the different sections of the route.

|

|

Tatyanna Isaacs leads the singing of passengers going to Juneau for a biennial gathering of Alaskan indigenous people. |

“The next time we’re up here, he’ll do the first half and I’ll do the second half,” Schlechter said.

While a clear chain of command exists, the way things are run tends to de-emphasize hierarchy. Crucial duties, notably lookout, are shared by everyone on the bridge. And the frequent switching of the conn also reinforces the idea that duties are shared.

While their workday is long — they report at about 0530 and are done by 1730 — the watches for the deck officers are short, about one and a half to two hours.

“We rotate,” Schlechter said, noting that the watches “kind of overlap.”

The frequent shifting of roles, combined with the relatively short watches, reduces monotony and resulting fatigue, helping the crew to maintain a maximum level of alertness.

Once Fairweather emerged from Peril Strait, it would enter Salisbury Sound. There it would make a sweeping turn to port and head for Neva Strait. While making the turn, the boat would be in unprotected water exposed to swells coming from the Gulf of Alaska.

As Fairweather approached Salisbury Sound, Krzesni alerted passengers that they should remain seated for the next 10 minutes.

To minimize passenger discomfort, the vessel is equipped with an active interceptor roll control system. Vertical blades at the stern extend or retract in response to accelerometers that monitor the vessel’s motion.

|

|

Fairweather’s wake is evidence of the vessel’s speed and power. The 235-foot ferry is propelled by four new MTU diesels that deliver 19,320 hp to the Kamewa waterjets, giving the ferry a top speed of over 43 knots. The vessel typically cruises at about 35 knots. |

The crew also does what it can to keep the ride as comfortable as possible. Stevens looked through her binoculars to examine distant rocks along the shore to starboard. The extent of the surf breaking over these rocks would indicate the size of the swells Fairweather would encounter, she explained. On this day the swell proved to be mild, but Schlechter still took the ferry through the turn on a line that would minimize the boat’s reaction to the swells.

In the open water, Fairweather was soon back to 35 knots, but as the strait narrowed, Schlechter brought it down to 18. Toward the end of Olga Strait, the final leg of the journey, the boat slowed once more, this time to 12 knots, the speed of a conventional ferry.

But conventional ferry it most certainly is not, a fact Schlechter never lets himself forget. Pointing to a settlement in an inlet off the port bow, he noted the need to slow the ferry so that its wake would not cause disruption along the shore.

“If we build up wake, it will go to that area,” he said. “It’s not a real high wake, but it has a lot of energy.”