Canadian authorities have issued new recommendations addressing mariner fatigue following the 2016 grounding of the tugboat Nathan E. Stewart near Bella Bella, British Columbia.

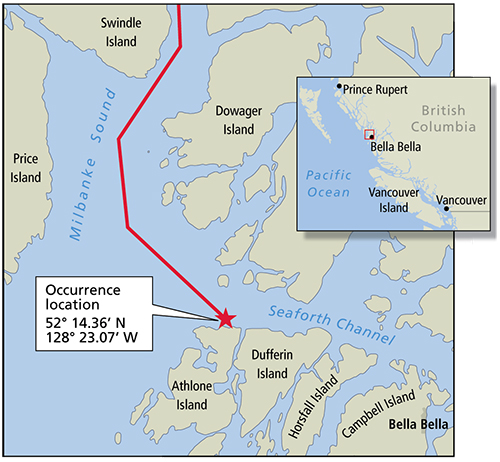

The second mate on watch fell asleep before the vessel and the empty DBL 55, the forward unit of the articulated tug-barge (ATB), struck a reef near Athlone Island at the entrance to Seaforth Channel at 0106 on Oct. 13, 2016. About 29,000 gallons of diesel fuel from Nathan E. Stewart escaped into the waterway.

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) determined that the crewman was fatigued, and it has called for mariners to undergo fatigue education and awareness training. The board also wants vessel owners to develop a “comprehensive fatigue management plan” tailored to their specific operation.

These recommendations are awaiting action by Transport Canada. But the TSB said they are intended to help mariners identify and prevent risks associated with the on-the-job reality.

“Although hours of work and rest requirements represent a layer of defense, they are not a guarantee that mariners will obtain adequate sleep. More is needed to effectively and reliably prevent fatigue among mariners,” the board said in its report on the grounding.

The TSB also highlighted recent research indicating “mariners’ compliance with regulatory work/rest scheduling requirements is generally poor.”

The second mate was alone in the wheelhouse at the time of the grounding, and the 3,400-hp tug was not equipped with a bridge navigational watch alarm. Other navigation alarms on the tug typically were not used, the report said. Wave and tidal action battered the tug’s hull against the reef, and the vessel eventually breached and sank.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reached a similar determination about the second mate falling asleep. The agency attributed the incident to crewmembers’ failure to follow watch-standing procedures in the Kirby Corp. safety management system. Kirby owned the vessel.

Nathan E. Stewart crew typically followed a four-on, eight-off schedule while underway, except during the 12 hours immediately before arriving in port and immediately after departing port. During those periods, the schedule shifted to a six-on, six-off rotation. The vessel, which was transiting from Ketchikan, Alaska, to Vancouver, British Columbia, operated on a six-on, six-off schedule for 58 of the 72 hours preceding the grounding.

The second mate slept less than 17.5 hours total during that time, and typically in the early morning after coming off watch. He never slept more than six and a half hours a day and slept as little as four and a half hours, the TSB said. The board likened those conditions to a typical person skipping an entire night of sleep.

“Opportunities to sleep were provided, but the second mate’s inability to nap, combined with the sleep-inducing conditions on the bridge, led to increased fatigue and resulted in the second mate’s falling asleep while on watch,” the TSB said.

|

|

A map provided by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada shows the ATB’s track line before the grounding. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

“Because deep sleep occurs primarily in the first half of the daily sleep period, it is likely that the second mate was obtaining sufficient deep sleep, but insufficient rapid eye movement (REM) sleep,” the report said. “Chronic restriction of REM sleep is associated with impaired cognitive function and increased fatigue.”

The report also noted crew are more likely to be fatigued following periods of varying watch schedules.

The difficulties of getting enough sleep while working aboard vessels have been well documented around the world. Fatigue has been a factor in at least 12 percent of the maritime casualties the TSB has investigated since 2002. The U.S. Coast Guard has explored fatigue and its effects, and in one study argued for moving away from the six-on, six-off schedule to give crew ample time for restorative sleep.

The TSB report highlighted potential benefits from changing start and end times for the six-on, six-off watch by three hours. This could effectively split the night hours — when staying awake can be most difficult — between two watch keepers. Such a change, the TSB said, “has been found to shift the risk of sleepiness and of falling asleep so that it is more equally distributed across bridge watch teams.”

Fatigue awareness and management programs also are not new. The U.S. Coast Guard Crew Endurance Management program addresses fatigue, and Canadian maritime pilots have been required to undergo fatigue training since 2003.

The program for Canadian pilots focuses on sleep fundamentals, signs of fatigue and coping strategies. Drinking caffeine, turning on bright lights, exercising, exposing oneself to cool air and engaging in conversation can provide short-term benefits against fatigue.

Conditions aboard Nathan E. Stewart on the night of the incident did not meet these best practices. It was dark, the heaters were on, light music was playing and the second mate was seated in a comfortable helm chair. He was also alone in the wheelhouse, with a tankerman on duty elsewhere on the tug.

“Consequently, the second mate was the single point of failure, with no other means, other than personal vigilance, of ensuring that there was an effective watch,” TSB investigators found.

Canadian authorities are drafting rules to require fatigue management training for masters and officers on vessels of 500 gross tons or larger. The TSB recommendations likely would expand on those standards to require that all watch standers undergo training focused on identifying and responding to fatigue while on duty.

The TSB recommendation that maritime companies create such comprehensive fatigue management plans would align the industry with existing protocols for the Canadian rail and air transit industries.

Kirby has since installed bridge navigational watch alarms on many of its tugs. The Houston-based firm also has implemented random vessel ride-alongs and has changed company procedures to require a second wheelhouse lookout while transiting pilotage waters.