Photos released by the National Transportation Safety Board show El Faro resting upright on the ocean floor, its superstructure broken off and lying a half-mile away. For veteran maritime accident investigator Hector Pazos, that means one thing: The wheelhouse was torn off the ship while it was still floating, likely with several crewmembers inside.

“To me, the … superstructure tearing away from the rest of the vessel is a situation that happened when the waves were hitting the vessel,” said Pazos, who has investigated maritime casualties around the world.

“My understanding of the pictures is that the superstructure became dislodged from the main hull, so evidently (there were) very strong waves and winds impacting the vessel sideways,” he said.

After losing its superstructure, Pazos said the ship could withstand the waves’ battering impact for no more than a few minutes before succumbing.

El Faro, a 790-foot roll-on/roll-off ship carrying containers and vehicles between Florida and Puerto Rico, had lost engine power and was drifting broadside to the waves as Hurricane Joaquin approached. The ship was taking on water and listing.

Richard Burke, professor of naval architecture and naval engineering at SUNY Maritime, argues that the 40-year-old ship probably met a slightly different fate. Like most experts, he believes the ship lost stability and capsized. The force of rolling over and hitting the water, he said, could have caused the superstructure to break away.

“I was surprised how it came off so cleanly,” Burke said of the superstructure. “It was like someone swept it off with a broom.”

Burke and Pazos are not involved in the federal investigation into El Faro, which sank on Oct. 1 about 35 miles northeast of Crooked Island in the Bahamas. Twenty-eight American mariners and five Polish contractors died in the incident, which spurred a massive search-and-rescue effort. In the weeks that followed, the Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) launched an extensive probe that could take years while never yielding conclusive answers.

The incident also spurred numerous lawsuits against TOTE Maritime and Sea Star Line, a subsidiary that operated the vessel, some of which the company recently settled.

|

|

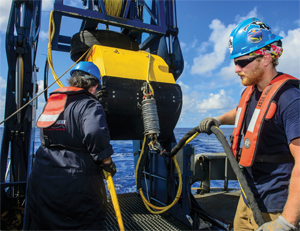

Contractors aboard USNS Apache deploy underwater search equipment on Oct. 19 in an effort to locate the wreck. The NTSB intends to search again for the missing voyage data recorder. |

|

Courtesy U.S. Navy |

Investigators found El Faro about 15,000 feet below the surface off Crooked Island in the vicinity of its last known location. However, authorities could not locate the ship’s voyage data recorder (VDR) among debris on the ocean floor despite an extensive search. The NTSB, which is leading the accident probe, announced on Feb. 11 that it would launch another search for the VDR, which could contain crucial details about the ship’s final hours. The decision to reconsider the search was spurred in part by a request from U.S. Sen. Ben Nelson, D-Fla.

The search is scheduled to start in April, and authorities will use an underwater autonomous vehicle to search roughly 13.5 square miles of ocean floor. The mission aims to recover the VDR and collect new photos of the sunken vessel’s hull, the debris field and navigation bridge, the NTSB said.

“The voyage data recorder may hold vital information about the challenges encountered by the crew in trying to save the ship,” NTSB Chairman Christopher A. Hart said. “Getting that information could be very helpful to our investigation.”

“Our original search mission provided us with useful information that may help us improve the chances of locating the voyage data recorder in a subsequent search,” NTSB spokesman Peter Knudson said. “Since that initial mission concluded in November, we have been evaluating the feasibility and cost of another search mission.

“We are looking at the availability of search and salvage assets, and the probability of success in finding the VDR capsule, among other factors,” he continued.

The decision to proceed with a second search mission coincided with a series of Coast Guard hearings on El Faro that began Feb. 16 and were scheduled to last 10 days. The agency convened a five-person Marine Board of Investigation to conduct interviews and allow interested parties such as TOTE to ask questions. Such hearings are rare, occurring most recently in the aftermath of the 2012 sinking of Bounty.

Specifically, the Coast Guard investigation will try to determine factors that led to El Faro’s sinking and whether misconduct, negligence, willful violation of the law or inattention to duty on the part of any licensed or certificated person contributed to the casualty outcome, said agency spokeswoman Alana Ingram.

Through separate investigations, the Coast Guard and NTSB are trying to find the cause of the sinking and identify potential safety recommendations. The Coast Guard has the authority to pursue civil charges if investigators find evidence of wrongdoing, Ingram said.

The Coast Guard and NTSB investigations could last until 2017, but lawsuits filed by the families of El Faro crewmembers could take even longer to resolve. In October, TOTE asked a judge to limit damages from the accident, arguing the company “exercised due diligence” to ensure the ship was seaworthy. The court set a deadline to file claims against the company for late December that was extended to mid-February.

|

|

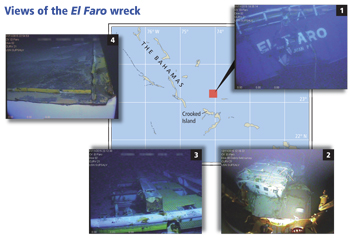

El Faro was found in 15,000 feet of water approximately 35 miles northeast of Crooked Island. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Photos courtesy NTSB |

Within that time frame, lawyers representing many of the 33 victims filed wrongful-death lawsuits alleging myriad problems with the vessel and the decision to sail into the approaching storm. The lawsuit filed on behalf of Addreisha Jones, widow of Jackie Jones, argues El Faro was overdue for repairs and not properly maintained in the past. It names Sea Star Line LLC, TOTE Services and ship Capt. Michael Davidson as defendants.

“Upon information and belief there were known issues with the steel of the vessel, including electrolysis and resulting corrosion, electrical issues, and its machinery and boilers needed service,” according to the lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in Jacksonville, Fla.

“These issues related to the condition of the El Faro which put the safety of the vessel and crew in danger, especially in heavy weather conditions where the vessel could foreseeably lose power or break apart.”

The suit claimed the ship lacked critical emergency equipment such as emergency position indicating radio beacons, or EPIRBs.

TOTE spokesman Michael Hanson said the company is not commenting on individual lawsuits out of respect for the legal process.

In late January, families of 10 victims accepted a settlement from TOTE worth $500,000 apiece for pre-death pain and suffering plus unspecified payments for future lost wages. The families of Davidson and the five Polish contractors on board were among those who accepted the settlement, according to media reports.

In a statement, Hanson confirmed the settlement but declined to confirm the value. He said the agreement was reached through a “respectful and equitable mediation process.”

Jack Hickey, a Miami attorney representing the estate of Louis Champa Jr. and one of Jackie Jones’ children, said in a phone interview that the settlement offer was much too low.

“In my opinion the $500,000 for pre-death pain and suffering is a pittance of what it’s worth and what they should be offering,” he said.

Hickey expects the discovery process to begin this spring, and he plans to “pursue vigorously” information about the cause of the accident. That will include communications between crew on the ship and the home office and with relatives at home, he said.

|

|

Federal investigators visit El Yunque, a sister ship of El Faro, at Jacksonville, Fla., on Oct. 9 to review equivalent characteristics of the lost ship, including the configuration of lifeboats. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

There are myriad theories about how the vessel went down, although most experts believe the stricken ship capsized. Capt. Robert Russo, who runs the Maritime License Training Center in Atlantic Beach, Fla., ran simulations last fall that showed a vessel similar to El Faro would likely capsize within minutes amid 35-foot seas and 70-mph winds — conditions less severe than what El Faro faced in its final hours.

However, those simulations do not describe what factors caused the vessel to lose propulsion or provide answers about conditions the ship encountered before going down. Burke believes El Faro lost engine power due to boiler water carryover after a period of heavy rolling. He suggested a “big flood of water” reached the engine and paralyzed the turbine, causing the vessel to drift and float broadside to the waves.

“The water starts to accumulate below deck in the vehicle deck, and loose water in a ro-ro is known to create a hazard through the free surface effect,” Burke said. “As stability is limited, the ship begins rolling more seriously and has much less ability to recover. At some point, a series of big rolls leads to the ship being capsized.”

He acknowledged this theory is little more than an educated guess, and said the chain of events leading to the sinking won’t be known for sure unless the VDR is found.

Russo, who lives near Jacksonville and planned to attend the Coast Guard hearings, said he hopes the probe sheds light on what happened. Regardless, he said the accident offers two important lessons. The biggest, he said, is the decision to sail into inclement whether. The second shows the importance of weather routing.

“If the decisions had been different, the outcome would have been different,” he said in a recent interview.

As the lawsuits move through the courts and the Coast Guard prepares for the hearings, Russo said the Jacksonville maritime community has more or less moved on from the accident. The only real discussion of the case he hears anymore is whether victims’ families should settle or fight on. None of the trainees in his licensing academy have dropped out because of El Faro.

“To me, that is saying something,” Russo said. “The community is accepting that this is something that has occurred and cannot be undone.”