Aboard the 74-foot canal tug Governor Cleveland, Capt. Mike Coon was preparing the boat for a voyage upriver, from Lock 8 on the Erie Canal to Amsterdam, N.Y. The purpose of the trip was to host an Erie Canal bicentennial event.

Since the 1950s, tug watchers have been on a restricted diet of commercial barge tows on New York state’s canals. They have, however, had the State Canal Corp.’s fleet of historic boats — vivid in blue and gold paint, polished brass and decked out with venerable machinery — to nibble on.

A modest increase in commercial cargo transport in the past decade also has given tugsters hope, but the big event in 2017 was the 200-year anniversary celebration of the legendary canal, which was built from 1817 to 1825.

“We’re an active tug for the Canal Corp.,” Coon said. “We push barges and scows in support of dredging and maintenance activities, and we participate in the occasional event.”

|

|

Governor Cleveland prepares to enter Lock 10 en route to Amsterdam, N.Y. High water is evident passing over the dam to the right of the lock wall. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

Record-setting rainfall in the Mohawk Valley last spring filled the Mohawk River, mother to 149 miles of the Erie Canal, with debris-laden water, causing lock closures. The Canal Corp.’s fleet of tugs, scows and barges had a busy time clearing the waterway. On June 9, with the last of the closed locks opening, it was time to put Governor Cleveland to work on the year’s celebrations.

Coon joined the Canal Corp. in 1997, crewing on Dredge No. 4. He made captain in 2001, first serving on Tender No. 3 and then as captain on the push tug Grand Erie in 2007. He was relieving Capt. Jim Boyce on Governor Cleveland for the Amsterdam event.

Gina Freeman, acting as road shuttle for the day trip to Amsterdam, arrived with coffee. She is the engineer aboard the 96-foot Grand Erie. In 2012, she married Chris Freeman, the engineer aboard Governor Cleveland, in Grand Erie’s engine room at the Waterford Tugboat Roundup.

“I learned machinery because of family history,” she said. “My father and brother had a shop and I liked to play around in it. I was a bit of a tomboy and loved to be in the shop.”

Governor Cleveland and a sister tug, Governor Roosevelt, were built specifically for the canals by the Buffalo Marine Engineering Co. in 1927 and 1928, respectively. In 1971, Cleveland’s two-cylinder J.W. Sullivan marine engine and Scotch Marine boiler were replaced with a 500-hp V8 Caterpillar engine. The workhorse tug is ice strengthened and rigged to push or pull scows and dredges.

|

|

After negotiating the strong currents, Governor Cleveland leaves the lock and continues its voyage upstream. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

At 8 a.m., Don Reilly, the maintenance assistant engineer, let go the line. Coon blew the whistle, swung Cleveland into the Mohawk River and headed for the weekend festival and fireworks in Amsterdam.

On July 4, 1817, ground was broken for the Erie Canal in Rome, N.Y. It was the passion of then-Gov. DeWitt Clinton, a project ridiculed as “Clinton’s Big Ditch” and “Clinton’s Folly.” DeWitt bore the scorn, and when the 363-mile project was completed in 1825, it was acclaimed as an engineering marvel and harbinger of an economic boom. Subsequently, New York City took its place as one of the great ports and financial centers of the world. Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse flourished and picturesque lock towns sprang up along the route.

Commerce, primarily raw materials, traveled east along the canal and south on the Hudson River to New York City and the Atlantic coast from the Great Lakes and the Midwest. Immigrants from Europe boarded boats and headed west on the canal. A six-week trip became a one-week trip and the cost to ship a ton of goods from Buffalo to New York City dropped from $100 to $10. The canal, completed earlier than expected and under budget, was paid for by tolls within 10 years.

In 1918, the New York State Barge Canal, the third iteration of the waterway, was completed. The project, abandoning a significant portion of the man-made channel, utilized the Hudson, Mohawk, Seneca, Oneida, Clyde and Oswego rivers. New dams and locks were built to accommodate larger barge tows.

|

|

Capt. Mike Coon finesses the wheel of Governor Cleveland as the tug prepares to leave Lock 8 in Glenville, N.Y. The destination was Amsterdam above Lock 10 for a celebration marking the Erie Canal’s 200th birthday. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

The height of commercial traffic on the modern version of the barge canal was in the 1950s, with cargo peaking at 5.2 million tons in 1951. Since the heyday of that decade, commercial traffic has been in serious decline, a victim of aggressive truck and rail transportation and the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959.

But a rebound is underway. In 2016, the waterway handled 163,671 tons of cargo, the most since 1993, the year the state’s canals were taken over by the New York State Thruway Authority. The name was then changed to the New York State Canal System, and two years ago the Canal Corp. was acquired by the New York Power Authority.

“The Power Authority is very adept at managing water issues and water projects,” said John Callaghan, the Canal Corp.’s executive deputy director. “They have seven power-generating facilities in the state, three of them on the canals. They know the importance of infrastructure to achieve functional, safe and secure systems. And they, as with the Canal Corp., have a strong sense of the proud tradition of the waterways.”

Callaghan said the Canal Corp.’s main focus last year was the bicentennial. “The Erie Canal is a world-famous brand and we have it right here, and we are definitely taking advantage of this major milestone,” he said. “The barge canal is older than its two predecessors combined. It’s in good shape, but we are conscious of its age and we have some decisions to make (to be) in better shape in the future.”

|

|

Governor Cleveland engineer Chris Freeman demonstrates how to use the Silent Hoist and Crane Co. capstan for making up a model-bow tow. He is married to Gina Freeman, who is the engineer aboard Grand Erie, a 96-foot push tug in the New York State Canal Corp. fleet. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

The Canal Corp., active and focused on increasing the visibility and benefits of the waterways for transporting commercial cargo, co-sponsored the annual meeting of the World Canal Conference in Syracuse in September. “It was a unique opportunity to gather people here from all over the world to discuss canal issues,” Callaghan said. “And with the bicentennial, it’s a good time to do it.”

A highly visible project marked the opening of the 2017 canal season, which was delayed by May’s high water. Twelve 20-by-60-foot fermentation tanks, too large for rail or highway transport, were loaded onto Coeymans Marine Towing barges and delivered by the tugs CMT Otter and CMT Pike from Waterford, on the Hudson River, to the Genesee Brewing Co. in Rochester, on Lake Ontario.

Genesee Brewing, piggybacking on the bicentennial, encouraged the public to line the canal to view the massive tanks shackled to the barges as they passed. An even more interesting sight was the double locking maneuver used to pass through chambers too short for the length of the tows.

Double locking entails the tow entering the lock and unmaking the lead barge. Then the tug backs out of the chamber with the second barge. When the water level in the chamber is equalized, the lead barge is winched out with the lock’s original capstan. The tug and second barge re-enter the chamber, lock through and the tow is remade.

Capt. Bob Clark, lead captain on the project aboard CMT Otter, said the most difficult part of the tow was the last 25 miles, beyond Lock 30 at Macedon. There the channel narrows and is winding, with docks and boats projecting into it. In order to negotiate the tight cluttered turns, it was necessary to proceed with one barge and then return light boat for the second barge. The procedure was repeated on the return trip.

|

|

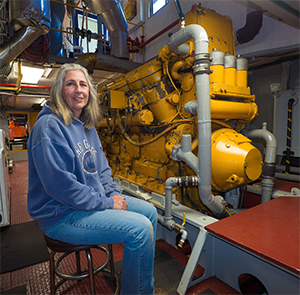

Gina Freeman, shown with one of Grand Erie’s two Caterpillar D386 12-cylinder engines, traces her interest in engineering to her family’s machinery background. “I was a bit of a tomboy and loved to be in the shop,” she says. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

“The tow went very well,” Clark said. “But the tanks are so high that at some of the bridges we had to nudge the first barge under the bridge with only a few inches of clearance, lower the wheelhouse below the height of the tanks and have the two ABs on the bow direct us. At some of the bridges they lowered the water in the pool for us to clear the bridge, and we had only a foot of water under the tow.”

A handful of tug and barge companies, including Coeymans, ply the state’s canals with commercial cargo. From Troy — 10 miles north of Albany at the eastern entrance to the Erie Canal and on the Hudson connecting to the Champlain Canal — a company called the New York State Marine Highway (NYSMH) conducts the lion’s share of the business. Rob Goldman, company president, is a passionate advocate for commercial transport on the state’s waterways.

Goldman’s mantra is, “We have forgotten why plants were built on the banks of rivers.” He extols the financial and environmental benefits of using water instead of rail or road to move commercial goods.

Project Cargo, the company’s division dedicated to high-value specialized projects and heavy-lift tows on the canals and Hudson River, has sustained the company through the lean years. Last year, NYSMH utilized its venerable tug Frances to deliver a transformer to the New York Power Authority’s international hydroelectric plant spanning the St. Lawrence River at Massena, N.Y.

Prior to 2016, the bulk of NYSMH tows linking the East Coast with the Great Lakes were conducted by the super canalers Frances and Margot. Then the company acquired five tugs to service a five-year contract barging a special grade of crushed stone for New Jersey-based Azzil Granite Materials from Lock 11 on the Champlain Canal to Long Island.

|

|

The 74-foot Governor Cleveland heads west on the Erie Canal after passing through Lock 10 at Cranesville, N.Y. Maintenance assistant engineer Don Reilly prepares a line on the bow. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

“The increase in equipment was huge for us,” Goldman said. “Our gross sales have gone up 50 to 60 percent and our staff the same. We have even had to create an HR department. We’re hitting our stride with the stone work, over 150 tons so far, and we’re now bringing back hauls of millings, busted-up paving material that is recycled back as filler in new paving to save on oil.”

For punctuation, NYSMH added another tug to its fleet last year, Nathan G., formerly Joan McAllister. “It’s a true creek boat, shallow draft, short, twin-screw, 1,200 horsepower. She’s perfect for delivering rock in the New York metro area creeks,” Goldman said.

Back aboard Governor Cleveland on the approach to Lock 9, Coon wrestled with strong side currents churned up by the high water gushing over the dam. Once in the chamber, Reilly coiled the mooring line and heaved it up some 15 feet to Freeman on the lock wall. Once the water in the chamber was equalized with the upstream river, Coon locked through and continued on to Lock 10.

Lock 10 brought more chaotic water. Coon, armed with a boatload of experience, maneuvered Governor Cleveland into the chamber. Bill Sweitzer, Canal Corp.’s marketing and media relations representative, boarded with a couple of journalists in tow. Coon locked through and made for the Amsterdam festival celebrating two centuries of Erie Canal history.