It was a chilly and misty Louisville, Ky., evening in mid-September, the kind of weather that cuts into an excursion boat’s passenger count. Still, a reasonable turnout of enthusiastic passengers warmed in the buttery glow of the interior lounges and dining room aboard Belle of Louisville. The revered steamboat, a National Historic Landmark, was one month away from turning the paddlewheel on a century of service plying America’s Western rivers.

In the pilothouse, Capt. Kevin Mullen and pilot Capt. Eddie Mattingly were preparing for a two-hour dinner cruise on the Ohio River. “For most of us this is more of an avocation than a job,” said Mullen. The people on this boat choose to work here and take care of the boat. The officers aboard did not learn by the book, they learned the old way — trained by guys who ran the steamboats in the 1930s.

As the 1900 departure time closed in, Mattingly, working the steering levers and spinning the 7-foot maple wheel, was warming up the steam-assisted power steering system. “This is done before every cruise and is necessary to drain any condensation from the steam lines and piston cylinder,” he said. “And just as importantly, this gives us early detection of any debris lodged in the rudders before departing the landing.”

In the engine room, alternate chief engineer Steve Mattingly (Eddie’s brother), and assistant engineers Dan Lewis and Tom Coursen were clustered around one of two pristine, double-acting reciprocating steam engines, circa 1890, perched in mechanical elegance and surrounded by tradition.

At 1830, passengers were boarding to the throaty notes thrust forth by the steam-powered calliope, one of only six left in the world. “It is loud, but it’s just a lot of fun,” said calliopist Martha Gibbs. “This is the most fun job I’ve ever had.”

Belle sparkled. It is one of three vessels owned by the Belle of Louisville, a nonprofit, city-owned entity, managed by the Louisville Waterfront Development Corp. The excursion vessel Spirit of Jefferson, built in 1963, and the historic lighthouse barge Mayor Andrew Broaddus fill out the fleet lineup. The barge, referred to as the wharf boat, is itself a National Historic Landmark housing the Belle of Louisville offices and maintenance shed.

Belle of Louisville was constructed in 1914 by James Rees & Sons Co. in Pittsburgh, Pa., as a ferry and packet boat bearing the name Idlewild. During World War II, Idlewild was fitted out for pushing barge tows on the river for the military and served as a USO nightclub for troops at various military bases.

|

|

Capt. Eddie Mattingly operates the engine-order telegraph and the 7-foot maple wheel. |

“She was bought by a Cincinnati company in 1947 (and) renamed Avalon and became a tramp steamer conducting river excursions on all of the Western rivers system,” said Capt. Mark Doty, ship’s master in charge of all three vessels. “She is the only authentic steamboat left from the American steamboat era, a 100-or-so-year run of water transportation that was, for the most part, displaced by diesel in the 1920s. She is considered the most traveled steamboat in history.”

In 1962 the vessel was in dire straits and narrowly avoided the scrap heap. Jefferson County Judge Marlow Cook bought Avalon at an auction for $34,000 and Louisville took the vessel under wing and rechristened it Belle of Louisville. “She was a rust bucket at the time,” said Doty. “Volunteers put her back together and made her what she is today.”

James McCoy, chief engineer for all three vessels, explained that if Belle had remained in private hands, the vessel would not have survived the 1960s. “We’re very proud of the Belle,” he said, launching into an explanation of Belle’s steam system.

The two engines were also built at Rees & Sons, circa 1890 — 25 or so years before the vessel was constructed. The horizontal cylinders have a 16.5-inch bore and a 6.5-foot stroke, producing a total of 450 hp. Each Pitman, the connecting arm that runs back from the engine and turns a crank on each side of the paddlewheel, is made of Douglas fir heartwood. The 24-foot-wide paddlewheel weighs 17.5 tons and is made of 16 white oak bucket planks. There are three 4-foot-by-9-foot rudders forward of the wheel.

When the engines are engaged in full stroke and running full ahead, they receive steam the entire length of the stroke. “Once the desired speed is attained, a cutoff is activated allowing steam to enter the cylinder at about 50 percent of the stroke. It is a variable cutoff so we can adjust this amount to any desired amount we want to run the boat most efficiently,” McCoy said.

While underway, the engine room is so quiet you can hear the shore traffic. The two pistons inhale and exhale at 11.5 to 12 rpm. “I worked out the torque the other day and it’s 240,000 foot-pounds,” Coursen said.

|

|

The paddlewheel, made of 16 white oak bucket planks, is 24 feet wide and weighs 17.5 tons. |

The boiler room, or firebox, is where the fireman stands watch and keeps the pressure on. The boiler, fabricated in St. Louis in 1967 by Nooter Corp., is a fire tube boiler with a common steam drum, mud drum and furnace. The boiler is fueled with No. 4 diesel. All three drums, under normal conditions, carry as much as 6,500 gallons of water.

The water is taken from the river into a settling tank, where any solids sink to the bottom, and then pumped into the boilers. The resulting steam is sent through overhead pipes to a collector drum and then to a throttle that controls the amount of steam injected into the engines to drive the pistons.

“Last year, Atlas Machine, a local company, re-bored the cylinders and fabricated new pistons and rings for us at no cost,” said McCoy. “It’s the first time work of this magnitude has been performed on these engines in more than 100 years of use. They’re basically new engines now.”

Back on the pilothouse deck, Mullen moved forward of the house and through a configuration of stay wires and passed the ship’s bell — vintage 1898 — onto the starboard wing bridge. From his perch, 130 feet forward of the house, Mullen became the pilot’s eyes. The walkie-talkie in Mullen’s hand is a modern concession used to communicate with Mattingly at the helm, as well as the deck crew.

“We use the headline to warp the stern of the vessel out into the river,” said Mullen. “The headline holds the bow in place to allow the stern to get out on the river. The distance the stern is out is dictated by wind and current. The more wind, the farther out the stern has to be. You learn to know when the Belle is out far enough by experience.”

In the pilothouse, Mattingly stepped on a foot pedal and Belle’s original steam whistle billowed a thick cloud of vapor and a long guttural signal that the vessel was about to leave the dock.

|

|

Assistant engineer Tom Coursen, right, stands watch at the engine-room telegraph, facilitating a 180-degree turn on the Ohio River with chief engineer Steve Mattingly looking on. |

Once Belle of Louisville gained the main channel of the Ohio River, the vessel proceeded upriver and made the Louisville bridges. Mattingly explained that at approximately six, 12 and 18 miles above Louisville, there is a series of three islands, named accordingly. They are used, among other landmarks, to aid the pilot in determining the appropriate turnaround points to keep the vessel on scheduled landing times. On a two-hour dinner cruise, Six Mile Island is the turn point.

In the engine room where the action takes place during a turn, Steve Mattingly explained that “there are always two engineers at the throttle while ‘handling’ the boat. It’s a joint effort between the engineers, the fireman and the pilot to keep the correct timing. She has a working Western rivers bell boat system, but we use annunciators.”

Coursen, surrounded by a configuration of levers and the telegraph, prepared to go into action. At his side, Mattingly stood ready to react in case a bell was missed or a mechanical malfunction interfered with the process. Mattingly relayed the bells to fireman Dan Lewis so that he could vary his rate of firing, depending upon the demands for steam.

A slow-ahead bell was the first indication that a turn was imminent. Hands in motion, Coursen answered the bell and disengaged the cutoff to return the engines to full stroke. He opened the scape pipes to relieve the back pressure on the cylinders from running at full stroke and adjusted the throttle to the slow position.

The next bell from the pilothouse signaled “all stop.” With hands flying, Coursen answered the bell, disengaged the engines and then reversed them, ending with the engines in the neutral position.

The next bell was a call for “slow astern.” Coursen answered the bell and re-engaged the engines.

|

|

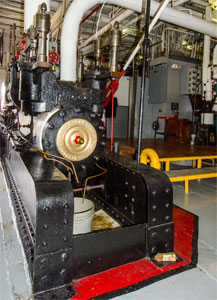

The Rees & Sons double-acting steam engine. |

With the turn nearly completed, the next bell was “all stop.” Coursen launched his hands, answered the bell, disengaged the engines and returned them to the ahead position.

Finally the bell called for “full ahead.” Coursen answered and grasped the ship-up jack, engaged the engines and opened the throttle to gain forward momentum. Once Belle was steaming and had established forward momentum, Coursen re-engaged the cutoff. With the cutoff engaged, he closed the scape pipes and adjusted the throttle to “full ahead.” His “Dances with Hands” performance was over for the moment.

Post-turn, a lull in the action was the signal for the stewards to ferry steaming trays of fried chicken, roast beef, fish and all the trimmings — leftovers from dinner supplied by Hall’s Catering — down to the engine room for the crew to feast on between maneuvers.

Approaching Louisville, a few passengers braved the brisk and misty air on deck to view the bridges silhouetted against the city lights.

In the pilothouse, Mattingly made the bridges and lined Belle of Louisville up with the stern of the wharf boat. Belle, not being the easiest vessel to maneuver in tight quarters, requires forethought, experience and patience to land. Wind and currents add to the currency of challenges. “Misreading them could put the boat and her passengers in peril,” he said.

Mullen struck out for his position on the starboard wing bridge as Mattingly brought Belle in at a very slow speed. “That presents challenges for the pilot because there is very little rudder control at the slow speed,” said Mullen.

|

|

Deck crew let go the lines using a steam-powered capstan. |

Mullen radioed Mattingly with boat-to-land distances and rudder and engine commands. In turn, Mattingly relayed them to the engine room via the telegraph. The engine room answered each bell and engaged the rudders and engine as required. Mullen incorporated the delay, inherent in the three-way procedure, into the timing of his instructions. “I listen to the scape pipes and can tell from the exhaust when the engines are engaged,” he said.

At about 30 feet from the wharf boat, and 30 feet from the concrete wall, Mullen instructed the deck crew to throw a line to the wharf boat. Employing the steam capstan on the bow, the deck crew pulled Belle forward. “It’s an 800-ton boat,” said Mullen. “But if we are going in too fast I can check the boat with the rudder. When the bow is in position, I position the rudders and back the stern into the wall. The goal is to have no bump. That is our measure of a successful landing, when nobody feels a bump.”

A month after that bumpless landing, McCoy reported that the centennial celebrations for Belle of Louisville were “a rousing success.” Capt. C.C. “Doc” Hawley was on hand to describe his early career on Avalon and his time as master of Belle. He noted that in 1975 he brought out the steamboat Natchez in New Orleans.

Joining the six-day party were the paddlewheel boats Spirit of Jefferson, Spirit of Peoria, Belle of Cincinnati and River Queen. Also on hand were the towboat J.S. Lewis, 98-year-old steam sternwheel towboat W.P. Snyder (also a Rees-built boat), sternwheeler Clyde and Capt. Tom Schiffer’s steam launch.

“That week alone the Belle carried over 5,000 passengers from far and wide,” said McCoy.