Coal passers have shoveled the black fuel into the stoker. A pair of Skinner Unaflow steam engines are churning at 95 rpm. The captain knows he’ll be pivoting off the anchor when it’s time to dock.

This moment in the life of a Great Lakes car ferry may seem to hearken to an earlier century — a long-lost era when America’s waterways teemed with steamships moving passengers and freight. This, however, is 2013, aboard SS Badger, the last coal-powered ferry still operating on the lakes.

The 411-foot Badger, a regional icon in its 60th year of service, still provides a vital link between Ludington, Mich., and Manitowoc, Wis. The four-hour crossing cuts travel time almost in half, compared with driving around Lake Michigan through Chicago.

|

|

Badger is an old-style “bell boat,” and Capt. Jeff Curtis still uses the wheelhouse’s engine-order telegraph to communicate commands to the engine room. |

At the helm of the old-style bell boat is Capt. Jeff Curtis, a former Great Lakes pilot who guides an eastbound August voyage out of Manitowoc. Curtis uses the engine-order telegraph — with its distinct combination of rings — to notify the engineers of the speed and direction he intends. When it’s time to land in Ludington, there are no bow thrusters or azipods to aid in the approach.

“I really enjoy the vessel. It’s unique. It’s ship-handling like the 1950s railroad car ferries, so it’s very different,” Curtis said. “This vessel has no bow thruster, and in this day and age you usually use a bow thruster or a tug. We use neither. We use the anchor.”

Operated by Lake Michigan Carferry Service, Badger steams across Lake Michigan at about 13.5 knots. Upon approach to the Ludington breakwater, the officers check for the landmarks they use to stay on the optimal track line.

“On the marshmallow!” is the cry as the ferry aims at a water tower, formerly nicknamed “blueberry” before it was painted white. The 4,244-gross-ton behemoth slows to less than 10 knots. Then it’s three blasts of the horn and a “half ahead” order.

When Badger eases past a condominium parking lot, Curtis achieves a hard turn to starboard with a “slow ahead” order on the 14-foot, four-blade port-side propeller and “slow astern” on the starboard prop. He drops the starboard anchor, which is always used in the maneuver and is particularly crucial in windy conditions.

|

|

Passengers gather on Badger’s bow to enjoy the sunset as the ferry departs Ludington, Mich., via the Pere Marquette River. Ludington Light is on the north breakwater, where the open waters of Lake Michigan await. |

“You release the wheelsman from up here to go back and tie up the stern and then you just use the engines. You move the vessel around just using the propeller,” Curtis said. “These techniques are not used a lot anymore. But they’re our bread and butter. … We drop the anchor and we start pivoting on the anchor. After I get the anchor down, I leave there and I walk to the aft pilothouse, and this happens on no other vessel that I know of.”

While the boat is turning clockwise, Curtis promptly exits the pilothouse and walks briskly all the way back to the stern pilot station to finish the docking by backing the ferry into the berth, with heaving line over, easing into the notches.

At Ludington, the pivot is 230 degrees on the starboard anchor. At Manitowoc, the turn is just 90 degrees on the port anchor.

Down in the engine room of Badger, Chief Engineer William Kulka is surrounded by old reliable machinery that they just don’t make anymore but is still getting the job done. Kulka was delighted when a visitor asked how much of the equipment is original to the vessel.

“Everything!” he said. “A few fluorescent lights have been added, but all the machinery and pumps are original. It’s 1953 when you step down here. We’re the last big coal burner in the U.S.”

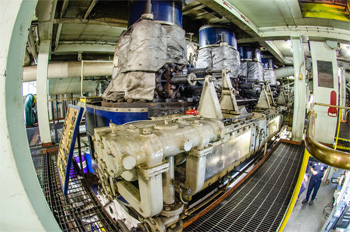

The two Skinner Unaflows — one of the last type of reciprocating marine steam engines — provide a total of 7,000 hp, aided by Hoffman Combustion Engineering mechanical stokers and four Foster Wheeler water tube D-type boilers. A pair of Warren Steam Pump Co. reciprocating pumps — “Bertha” and “Betty” — are positioned fore and aft.

|

|

Donald Short, senior wheelsman, started working on the ferry in 1970 as a deck hand. |

The engineering watch includes at least one engineer plus an oiler, water tender, fireman and coal passer. Kulka’s crew are keenly aware that they’re literally keeping history alive with every rpm. The first assistant engineer, Kevin Diedrich, 53, takes pride in properly maintaining the old equipment.

“I like it because of the nostalgia, and this is how they did it years ago,” Diedrich said. “That’s neat. You can’t just flip a switch. You have to know it intimately.”

Before joining Badger, Diedrich served aboard a Coast Guard buoy tender. “On there you might have to replace a pump. You take the old one off and put the new one on, and that’s it. Here we might have to have parts made. It’s a challenge,” he said. “So it’s satisfying when the plant is running real good.”

Besides the fully functioning engine-order telegraph, another old friend still in Badger’s wheelhouse is a Mackay radio direction finder, which in earlier days pinpointed radio signals from lighthouses, but today is no longer in use.

Although the boat’s officers take pride in their traditional seamanship techniques, they also rely on their modern bridge technology. The wheelhouse is equipped with Raytheon R21 raster scan radar and Furuno FR-2830S radar, as well as Furuno GP-150 global positioning and Universal AIS, plus a Sea 157 VHF radio telephone.

The AIS is particularly useful in anticipating crossing arrangements involving other large vessels. The captains often gauge Closest Point of Approach while checking the track lines of frequent Lake Michigan visitors such as the century-old 551-foot cement carrier St. Marys Challenger — coincidentally powered by similar Skinner Unaflow engines — in possibly its final year of service as a self-propelled vessel. On this day, Badger’s AIS also was tracking tugboat Leonard M. with its barge Huron Spirit and the tug John M. Selvick.

|

|

One of Badger’s two steeple-compound Skinner Unaflow reciprocating steam engines. |

During warm weather, Badger must navigate amid crowds of fishing boats and other pleasure craft, especially along the Manitowoc and Ludington shorelines. The captains warn “Watch your ears!” before each loud horn blow.

On the approach to Manitowoc, Senior Captain Dean Hobbs likes to use the formal master’s salute — three long blasts and two short blasts.

“It’s like a parade here every night in the summertime,” Hobbs said. “Most of them are pretty aware of us. The reason I like to blow all these salutes is I prefer doing the salutes to danger signals.”

Residents in both Manitowoc and Ludington never get tired of visiting the waterfront to watch Badger come in. The boat is registered as a historic site by the states of Michigan and Wisconsin. Aside from the nostalgia, the ferry is a crucial twice-a-day transport connection not only for tourists but also for diverse freight. The capacity is 620 passengers and 180 autos. The boat serves as a mini hotel, with 40 staterooms. It carries 50 to 60 crew, including 15 watch-standers.

The boat recently carried the Budweiser Clydesdales and has a contract to ship Broadwind Energy wind-turbine tower sections, which are fabricated in Manitowoc.

|

|

Keeping Badger’s machinery working are Kevin Diedrich, Jim Fiers, Phyr, Jeremy Piper, Chief Engineer William Kulka and Dave Wirt. |

“There’s a lot of support for the Badger in both communities. They consider the Badger to be their own. They don’t want to see it go away,” Diedrich said. “And I’m part of it, and I’m proud of that fact. When I look in there and see that crankshaft spinning around, that’s something that I never get tired of looking at.”

Over the years, the coal-fired ferry’s future was anything but guaranteed. The last of seven Ludington-based rail car ferries, Badger was out of service in 1990-91 due to bankruptcy. Environmental controversies arose beginning in 2008. On a daily basis, the engineering crew discharges tons of coal ashes by blowing them into Lake Michigan with an “ash gun” while the ferry is on the move. In a regulatory process that had threatened to shut down the coal-fueled boilers forever, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 2012 extended the boat’s permit for only two years.

Badger does appear to have a new lease on life. In a consent decree signed in October 2013, Lake Michigan Carferry Service promises to end the ash discharges by the 2015 season and, in the interim, to use stoker coal with less ash and mercury content. Beginning in 2015, ash from the boilers will be retained aboard the boat for disposal at a land-based facility.

“We’re very optimistic that we’ll be here for a long time,” said Chuck Leonard, the company’s vice president of navigation. “These people take pride in the unique vessel they operate. I take pride in being involved in it. And that is why we’re striving so hard to ensure the future of the vessel.”

|

|

Exodus Phyr, a water tender, watches the engine-room gauges and chadburn. |

Leonard’s office is on the Ludington side, in the shadow of Badger’s sister ship, SS Spartan, which has been tied up since 1979 and is still used for replacement parts.

In the bowels of Badger’s propulsion plant, Kulka points out another relic from days gone by. Next to the stokers sits a “trophy bucket” full of “boiler clinkers.” The firemen and coal passers occasionally find foreign objects in the coal shipment, and those items are removed and placed in the bucket. “Rocks. Railroad spikes. Big carriage bolts. Chunks of metal. Blasting wire. The stokers take a beating,” Kulka said.

Kulka identified aspects of the boat that hearken back to its service to the railroad. “The (two) reciprocating steam air compressors are right off a locomotive — the exact same model! — right out of the C&O warehouse, and they ended up at the shipyard,” he said. Badger was built by Christy Corp. at Sturgeon Bay, Wis.

|

|

Passengers play “Badger Bingo” during the ferry’s Michigan-bound crossing. Badger is a vital link for Great Lakes tourists and trucked freight. |

Upon nighttime arrival at the Manitowoc breakwater, Hobbs uses his own set of pilotage landmarks — a smokestack, church steeple and chain-link fence. He shines a spotlight toward the area of the berth before turning hard right.

“I slow the boat down, and I wait off the apron, and our first line ashore is on the bow,” Hobbs said. “Then I notch up.”

Hobbs knows his exact position because he receives verbal reports from the deck crew: “One wire on … 30 feet … 20 feet … 10 feet … up against … notch up.”

SS Badger completes another landing. The crew, management, tourists and local residents hope there will be many more.