The meeting or head-on situation often receives brief treatment in nautical treatises due to the common perception that it presents little danger to the vessels involved. However, the meeting scenario presents a unique set of challenges that the prudent mariner must consider.

There is a potential for delayed detection of the other vessel as a result of the reduced radar cross-section and visual profile of the vessel. This is compounded by the high relative speed of the vessels, which has the effect of reducing reaction time and increasing collision forces.

The meeting/fine crossing situation can lead to confusion of status and responsibilities between vessels, according to Craig H. Allen, University of Washington law professor and retired U.S. Coast Guard officer who is a recognized authority on the ColRegs.

“The inherent ambiguity in many recurring meeting scenarios creates a danger of conflicting action by the approaching vessels,” Allen noted in the eighth edition of Farwell’s Nautical Rules of the Road.

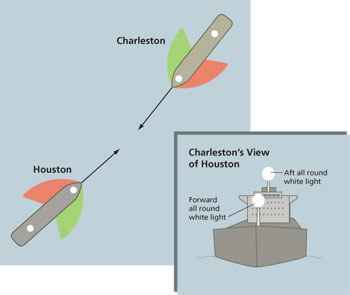

Consider the following hypothetical scenario. It is a calm, clear day off the coast of Cape Hatteras. You are the watch officer on the 950-foot containership MV Charleston, just south of the cape and on a southwesterly course bound for Charleston, having departed Chesapeake Bay the previous night. M/T Houston, a 550-foot petroleum product carrier, is on a northeasterly course to clear the cape on its way to Delaware Bay. There are no other vessels of concern nearby and visibility is unrestricted. At the time you sight Houston, it is one point on the starboard bow heading generally in the opposite direction and showing a slight port aspect.

You begin to track Houston on radar and, while the ARPA develops a plot, you run through the possible maneuvering scenarios in your mind. Will both vessels pass starboard to starboard with no risk of collision? Will you be required to maneuver? If you are required to maneuver, are the two vessels meeting head-on or are they crossing? If you turn to starboard, will the other vessel turn to starboard as well? After several minutes, the radar shows Houston as eight miles away and the ARPA has calculated a 0.1 nm closest point of approach. If any maneuver is required, you will have to act soon.

Part B, Section II, of the ColRegs governs the conduct of vessels when in sight of one another. While these rules are simple in their design, determining which rule is applicable in a given situation can be more complicated. This holds true in the meeting/fine crossing situation described above, which may be interpreted as either head-on or crossing by the vessels involved. The professional mariner must be able to quickly and efficiently determine when such a situation exists, what rules to apply and how to avoid confusion with the other vessel involved.

ColRegs Rule 14 governs meeting or head-on situations and states that “when two power-driven vessels are meeting on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve risk of collision, each shall alter her course to starboard so that each shall pass on the port side of the other.”

ColRegs Rule 15 governs crossing situations and states that “when two power-driven vessels are crossing so as to involve risk of collision, the vessel which has the other on her starboard side shall keep out of the way and shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, avoid crossing ahead of the other vessel.”

The initial consideration, regardless of whether it is a meeting or crossing situation, is whether risk of collision exists. ColRegs Rule 7 states that “every vessel shall use all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions to determine if risk of collision exists. If there is any doubt, such risk shall be deemed to exist.” Considerations in this determination include situations involving constant bearing and decreasing range, as well as situations involving large vessels. If risk of collision does not exist, then the vessels need not maneuver and may pass as their present courses and speeds allow.

If, however, risk of collision does exist, then the mariner must engage in a secondary analysis and make a determination as to whether this is a meeting situation governed by Rule 14, or a crossing situation governed by Rule 15 in order to clarify the responsibilities of the vessels.

Paragraph B of Rule 14 provides two criteria for establishing whether another vessel is on a “reciprocal or nearly reciprocal” course such that they are meeting. The first requirement is that the vessel be “ahead or nearly ahead.” The second is that the vessel’s keel be aligned so that by night its masthead lights appear “in a line or nearly in a line” and both its sidelights are visible, and by day it shows an equivalent aspect of her hull and superstructure. Both of these requirements must be met in order for a vessel to be on a reciprocal course.

The definition of “ahead or nearly ahead” is not provided by the ColRegs and the interpretation of the term can vary widely among mariners. Some may consider a vessel on a course that is only one point off the bow to be “nearly ahead.” After all, one point out of 32 on the compass does not seem like much of a difference. However, Allen suggests that “the weight of authority supports the conclusion that a vessel should be considered nearly ahead … if, when risk of collision arises, her relative bearing is within one-half point (five to six degrees) of the bow.”

In determining the alignment of another vessel ahead or nearly ahead, the watch officer must consider the totality of the visual information presented. For example, the presentation of the masts of a ship by day may not provide as precise an indication of the alignment of the vessel as would the presentation of the masthead lights by night. Another consideration is that the sidelights of another vessel may not show exactly the horizontal arc of visibility prescribed by the ColRegs, so that both sidelights may be visible when the masthead lights are not in a line.

Assessing the maneuvering situation with Houston, the watch officer aboard Charleston can confidently determine that the situation does not meet the requirements of Rule 14. While Houston is generally ahead of Charleston, it does not appear so close to the bow as to be considered “ahead or nearly ahead.” Houston is also showing a slight port aspect, which suggests that its masthead lights, if visible, would not appear in a line. These two criteria considered together suggest that Charleston is not in a head-on situation with Houston.

Nevertheless, it is still quite possible that a watch officer in this situation could consider it to be a head-on situation. The relative bearing of Houston and the slightness of its port aspect may suggest that the vessels are meeting on nearly reciprocal courses. There is also the catchall character of Rule 14, which directs the vessel to follow that rule if there is any doubt as to whether a head-on situation exists. Fortunately, the ColRegs reduce this confusion by directing both vessels in a head-on situation to alter course to starboard. If either Charleston or Houston misconstrues the scenario as a head-on situation, one or both of the vessels are obligated to alter course to starboard, reducing the risk of collision.

Having ruled out a head-on situation in this scenario, the watch officer aboard Charleston must now consider Rule 15 of the ColRegs, governing crossing situations. The standards for applying Rule 15 are very simple: There must be risk of collision and the vessels must be crossing. The ColRegs do not define “crossing,” though it is readily apparent that any two courses will cross at some point unless they are exactly parallel. Because the watch officer on Charleston has already determined that Houston is neither on the same nor a reciprocal or nearly reciprocal course, the situation must be a crossing one.

Rule 15 requires that a vessel in a crossing situation keep out of the way of a vessel on its own starboard side. This is usually accomplished by an alteration of course to starboard when there is plenty of sea room, but may also be accomplished by a change of speed or a combined change of course and speed. For the watch officer on Charleston, the safest maneuver is to make a substantial course change to starboard that will put Houston on its port bow and allow Charleston to pass safely astern of Houston. In making the course change, Charleston should consider the new aspect that it presents to Houston. By showing its red sidelight and separated masthead lights, or an equivalent daytime aspect, it will make it clear to Houston that Charleston has taken appropriate action.

One last consideration should be taken into account in the head-on/fine crossing situation. It is possible that in areas with strong wind or current, vessels may be on reciprocal courses even though they are not on reciprocal headings. Likewise, two vessels may appear on reciprocal headings and not be on reciprocal courses. It is important that the watch officer consider all the available information in determining which type of maneuvering situation exists and, if possible, avoid making a course change to port.

As this meeting/fine crossing scenario illustrates, the professional mariner must be able to engage in quick and efficient analysis of an approaching vessel’s relative bearing and course when determining whether and how to maneuver in accordance with the Rules of the Road, as even a seemingly innocuous situation such as this can present a significant risk of marine casualty when the nature of the vessel’s position and movement and the respective responsibilities between vessels are not fully appreciated.

Samuel R. Clawson Jr. is an attorney with Clawson & Staubes LLC in Charleston, S.C., who holds an unlimited tonnage merchant marine deck officer’s license and has sailed for a major international container liner. He has lectured and authored articles on topics including terrestrial navigation, Rules of the Road and STWC and MARPOL compliance.

Stephen W. Scott is a professional mariner who holds an unlimited tonnage merchant marine deck officer’s license. He has experience sailing on many types of vessels, including fishing, towing, break-bulk and tank vessels. He is currently a first officer with the Military Sealift Command.