After John McKay graduated from high school in 1917 and began looking for a job, one docked at his feet.

The 17-year-old was walking along the Brooklyn waterfront near his Greenpoint home with no interest in a maritime career. But then “a tug came in and they were ‘grubbing up,’ which meant they were coming in to get food for a trip,” related his daughter, Margaret Therese McKay Egan, who goes by Therese. “He was kind of walking past the tug and looking to see what it looked like, and the captain called out to him, ‘Want a job?’

“And of course my father grabbed at the opportunity and said yes, he would. And the captain said, ‘Hop aboard.’ He said they would be leaving for Port Arthur, Texas, in a half-hour. And they did, and that was the beginning of his career. He didn’t even have time to tell his family. He was just so happy to get a job (that) he went along. I guess he called his family when he got to Port Arthur.”

That trip marked more than the beginning of a long career in the towing industry for McKay. It began a family legacy of working on tugboats that has extended for two more generations as well as expanding to other relatives.

|

|

Patriarch John McKay took his first maritime job aboard a Texas-bound tug in 1917. |

|

Egan family photo |

Recently, Therese and her husband, second-generation tug captain John Egan, were joined at the Whisper Woods assisted-living facility in Smithtown, N.Y., by their son John Jr. and his wife Linda to tell the family’s tugboat story. Therese and John Sr. are residents at the facility.

Therese — the 90-year-old daughter, wife and mother of tugboat captains — said her father started out like all new hires as an oiler. He was promoted to deck hand, mate and eventually captain, a position he held for four decades. He only worked on tugs in New York Harbor and only for one company, Russell Brothers Towing. He remained on the job until he was nearly 70, spending the last few years ashore in a management position.

“He liked it and thought it was a wonderful industry,” Therese said. Nonetheless, his advice to his children was to get an education and work shoreside.

His children listened, but his future son-in-law ignored him.

|

|

John Egan Jr. holds sons Owen, now 21, and John III, now 24, in 2002. Egan, who started as a deck hand with Eklof Marine in 1984 and became a captain in 1997, has worked on the Gulf Coast for Kirby Offshore Marine for the past seven years. |

|

Egan family photo |

John Francis Egan, now 91, started dating McKay’s daughter Margaret Therese, who grew up on the same street, when he was 16 or 17. Just as McKay had done when he graduated from high school, Egan was looking for a job at age 17. Because of his connection to the McKays, he asked his girlfriend’s father about getting into the towing business. McKay repeated the advice he had given his own sons.

Egan, known in the family and the trade as Capt. Jack, wasn’t persuaded. Like McKay, he had no interest in a maritime career initially. “I wanted a job,” he said. “And that was what I knew. In high school, he would take me out on tugs for a day at a time.”

But when he applied for a job at Russell Brothers, McKay blackballed him.

“So, I went to Moran. I started as an oiler” just like McKay, Egan said. He spent about three years in the engine room before being promoted to deck hand. After the first two years, McKay relented and hired him at Russell Brothers. It took Egan about 15 years of tug work to make captain, a position he attained before he married Therese in 1953.

|

|

John Egan Sr. dresses for the part as a sea scout at age 12. |

|

Egan family photo |

Most of his work was going up the Hudson River, along the Erie Canal and out into the Great Lakes and back, towing or pushing petroleum barges. But he did travel as far as South America — on his first trip.

Egan said what he liked most about tug work was the camaraderie among the crew of 10 to 12. “We were very close,” he said. “It was like a family.”

The downside of the job was long separations from loved ones. Initially, “it was months,” he said. But as he moved up in seniority, “it was two or three weeks on and two or three weeks off.”

When Egan was working, he’d be on duty for six hours and then off for six. It could be dangerous work. “One time my hand was caught in the engine rocker arm and I broke several fingers,” he said. On another trip, a crewman fell overboard and was never recovered. “We had some pretty bad storms on the Great Lakes,” he recounted.

|

|

John Egan, at left, stands with son John Egan Jr. aboard the Eklof Marine tanker Reliable II. |

|

Egan family photo |

Egan, who retired in 2005 after suffering a heart attack, never tried to dissuade his son from a career on tugs. “I got into it by default, I guess,” said John Egan Jr., 57, a resident of East Northport on Long Island. “During the summer months when I was in junior high school, I would go to work for a week or so with my dad,” he said. He started out as a passenger but eventually began to work part time doing maintenance on deck.

After graduating from high school, he attended a union training school in Maryland, joined the Seafarers International Union and went to sea without ever considering any other kind of work.

John Jr. started out sailing “deep sea” for three years on cargo ships traveling to Asia or Europe. “But I always knew I was going to end up in New York Harbor and get into the tugboats,” he said.

By then his father was working for Eklof Marine, so John Jr. worked there as well, starting as a deck hand in 1984. A little over a decade later, he had earned his mate’s license and by 1997 he was a captain, initially working out of Staten Island.

|

|

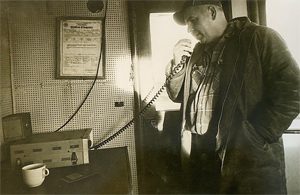

Egan works the radio on the bridge of the tanker Jet Trader. |

|

Egan family photo |

“The whole allure of the job is equal time,” John Jr. said. Crew scheduling has changed in the industry since he got started, “but I was lucky enough to get into the business so I would be away for a week and then be home for a week. Then gradually it worked into two weeks away and two weeks off, and now I’m working three weeks away with three weeks off. You can’t beat the off time. But it’s always hard to go back to work. The last few days at home I’m sort of in a bad mood.”

John Jr. and Linda have been married for 25 years. She said the unusual work schedule “actually works great for John and I because we got married in our 30s, so we were used to being on our own. It was when the kids (John III and Owen, now 24 and 21, respectively) came along that it was a little difficult for them when they were little and he would leave.”

“I’ve been lucky enough to basically stay with the same company for my whole career,” John Jr. said. “Eklof was purchased and became K-Sea (Transportation Partners) and I stayed with them for 10 years, and they were then bought out by Kirby Offshore Marine. So the company gradually got bigger and bigger and bigger, and their geographical footprint expanded.”

He started primarily working out of New York Harbor with the occasional trip to Boston, Maine, Philadelphia or Norfolk, Va. For the past seven years, he has worked along the Gulf Coast for Kirby. His current tug is the 121-foot Heath Wood, delivered in 2016 and named after a deceased Kirby engineer. On his most recent trip, he took that tug from New Orleans to Los Angeles through the Panama Canal, his first transit of the waterway.

|

|

Father and son look back fondly on their days at sea with the help of family snapshots. |

|

Bill Bleyer |

John Jr., who typically works a 12-hour shift overseeing 11 or 12 crewmembers, said running a tug is a demanding job that is “getting harder every day. There are new rules and regulations and policies and procedures.”

“What I like about the job is that you have camaraderie out there,” he said. As with the prior generations, “we’re always dealing with weather issues. About a year and a half ago, we had a storm in the Gulf of Mexico that came through strong and hard for about 12 or 15 hours. In my career, going back to 1984, I never saw weather like that. I was on my way from Corpus Christi to New Orleans and we had to divert to Houston. I’ve never had a vessel roll over so far in my life. The waves were 20 to 25 feet high, with winds of 55 miles per hour.”

The McKay-Egan tugboat family tree includes John Jr.’s uncle, Jim McKay, who was an engineer on Eklof tugs. Jim’s son, also named Jim, originally from Wantagh, N.Y., but now living in North Carolina, is a captain working for Kirby. The younger Jim’s two sons also work for Kirby. Another of John Jr.’s cousins, John McKay, works on the water as a Hudson River pilot after working with the elder John Egan on tugs for a short time.

But the family’s tugboat saga won’t have a fourth-generation chapter. Although he took them out on tugs during vacations as they were growing up, John Jr. said his two sons “never expressed any interest” in pursuing a maritime career. They are currently working in retail sales.

“It wasn’t for them,” he said. “In this kind of job, you really have to want it.”