Regulations under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) state that if asbestos is found on board a ship built after July 2002, then the vessel’s flag registry, in conjunction with its classification society, issues a non-extendable exemption certificate, providing the owner with a three-year window in which to remove the asbestos.

Any ship built before 2002 may contain asbestos but must have a hazardous materials’ register and management plan in place to cover any maintenance or repair work involving asbestos. This situation could be considered somewhat ridiculous and, while originally it might have been thought a straightforward move to ban asbestos in ships built after 2002, the reality is that we have a system that’s failing.

It’s possible to correct this by ensuring that all new vessels have an approved asbestos survey before they are delivered to operators, but there are significant logistical challenges ahead.

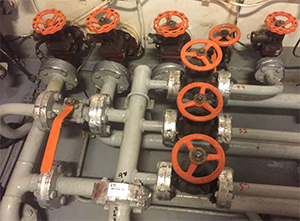

In the European Union (EU) alone, there are 30,000 ships requiring an inventory of hazardous materials (IHM). Of these, it’s estimated that 80 percent will contain some form of asbestos. But what does an IHM inspection involve? An accredited surveying company carries out an inspection to verify the amount of hazardous materials on board a vessel — 60 percent of which is an asbestos survey of the ship’s systems and structure (it is well documented that 80 percent of existing and new ships contain asbestos in their systems).

The amount of asbestos found on board depends on several factors, including where the ship was built. In our experience, ships built in the Far East and Turkey have a high percentage of items containing asbestos. Ships also can be contaminated through items brought on board by the owners, despite assurances that they are asbestos-free.

The term “asbestos-free” can be a misleading one due to the different international standards that constitute exactly what it means. In the United States, for instance, it is up to a 1 percent content, while in the EU it is 0.1 percent and 0 percent in Australia. In the Far East, China has no official standard — indeed, we have found as much as 15 percent asbestos in materials that have been declared free. The problem is compounded by the fact that there is no testing and certification of materials by manufacturers.

Global supply chains are such that a lot of material and equipment originates from China, where it is still legal to use asbestos. Chinese manufacturers may set up a production line to supply “asbestos-free” materials, but they also could be unaware of cross-contamination in their factory emanating from other production lines that are producing items containing asbestos.

The usual procedure is for a shipyard to issue a declaration that its vessel is “asbestos-free” before the classification society makes a notation to that effect on the operating certificate based on a statement of fact. However, government-flag states such as Australia and the Netherlands are aware that these declarations can be inaccurate, and insist that a ship registered under their flag has a verification asbestos survey performed by a marine specialist ISO 17020 accredited company and that any asbestos found is removed before the ship can be registered.

For some reason, Panama, Liberia and the United Kingdom, among other major flag states, still accept a classification society’s inspection for an annual operating certificate even though the “asbestos-free” notation is based only on a shipyard declaration that the vessel is “asbestos-free.”

So, what can be done to ensure an asbestos-free ship? There are some important steps to take, but it’s important to engage the services of an ISO 17020 accredited company, which has the experience and resources to undertake a comprehensive survey. Then, if asbestos is found, have it removed and instigate a quality management system that periodically has materials supplied to the ship tested to see if they are safe. After a refit, it will be important to undertake an update survey.

A proactive prudent approach can prevent potential litigation for claimed exposure to asbestos from the ship’s crew, protecting shipowners. It also can enhance the true value of the ship and eliminates any potential issues if asbestos was found during a pre-purchase survey and, ultimately, protects the crew and anyone else working on the ship.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) would be justified in modifying the SOLAS requirement for asbestos in ships and institute a more manageable procedure that would contribute to securing the safety of seafarers. This modification also would spur owners into actioning the IHM inspections now rather than leaving it to the last minute. It really is matter of urgency, therefore, that the following principles are adopted by the EU and Hong Kong Convention as an approved amended regulation:

• All new ships must have an accredited asbestos survey.

• All existing ships must have an asbestos survey performed by an accredited marine specialist ISO 17020 survey company. This can be part of an approved IHM survey.

• If asbestos is found, then an asbestos management plan should be established. All high-risk asbestos should be removed within three years. Low-risk asbestos items should be encapsulated and replaced when maintenance requirements allow, and condition monitoring should be recorded.

Looking to the future, we are seeing some flag states adopting a more realistic approach by accepting an asbestos register and a management plan for ship operations, and in planned refits and maintenance overseen by licensed contractors working on site to ensure the safe removal and management of asbestos-containing materials (ACM). The flag state may accept this beyond the three years as an equivalence to the removal of ACM with a certification to the vessel and notification to IMO accordingly.

John Chillingworth is a former chief engineer on Cunard Line’s QE2 liner and marine technical manager who has more than 27 years’ experience in dealing with marine asbestos and hazardous materials. He is currently a senior marine principal at United Kingdom-based Lucion Marine. The firm provides specialist environmental services to the international marine sector, specifically providing advice on the management of hazardous materials to both working and end-of-life vessels.