In 2006, General Dynamics NASSCO took on a five-ship contract to build product tankers for U.S. Shipping Partners LP. The result was the State class, a series of 600-foot, double-hulled Jones Act ships based on an existing design from South Korea’s Daewoo Ship Engineering Co. (DSEC).

A decade later, the San Diego shipyard has taken tanker construction to the next level, rolling out the ECO class for American Petroleum Tankers (APT) and SEA-Vista. While the 610-foot ships carry roughly the same volume of product as the State class, hull optimization and other technological gains allow the new tankers to deliver a 33 percent boost in efficiency — cutting fuel consumption by the equivalent of about 10 tons of fuel per ship per day. In another nod to the environment and cost savings, the ECO class is designed to accommodate a future shift to dual-fuel propulsion with liquefied natural gas.

As of midsummer 2016, NASSCO had delivered three ECO-class ships to APT and one to SEA-Vista, a partnership between SEACOR Holdings and Avista Capital Partners. Two more are on the way for each owner. Like the other ships in the series for APT, the second — Magnolia State, delivered in May 2016 — follows a naming scheme that started with the previous tankers from the yard. The original State class, also known as the PC-1 class, began with the delivery of Golden State in 2009 (it was American Ship Review’s Ship of the Year). The first ship in the ECO series was Lone Star State, delivered in December 2015, and Magnolia State was followed by Garden State in July 2016.

|

|

The ECO class features a raked stern that is complemented by a full-spade rudder. |

Moving beyond the monikers, there are a lot of differences between the State and ECO classes, despite the tankers’ similar size (600 and 610 feet, respectively) tonnage (49,000 dwt and 50,000 dwt) and cargo-carrying capacity (331,000 and 330,000 barrels). The two biggest differences involve the ECO class’s hull form and engine technology.

Parker Larson, director of commercial programs for NASSCO, said the State-class tankers were based on merging two parent designs: one a hull design and one an equipment design. The ECO class is cut from a new blueprint with a completely different hull.

“If you look at the hull form of the ECO class and compare it to the hull form on the State class, the State class looks like a big box,” Larson told American Ship Review during a visit to the San Diego yard in mid-May. “(The new tankers) actually have a hull form that’s closer to what you would see in a containership. You can really see it in the shape — there’s virtually no parallel midbody. It just immediately gets into the curved shape of the ship, both fore and aft. It goes through the water very smoothly, which was proven during sea trials.”

|

|

Garden State awaits completion at NASSCO in May alongside Magnolia State. |

Larson said that when the State class began to come to fruition early in the past decade, fuel efficiency wasn’t as much of a driver as it was when the ECO class was designed. When NASSCO signed on to build the new tankers, fuel prices were high and there was a big push internationally for ship designers to produce the most efficient vessels possible. DSEC, a subsidiary of Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, rose to the challenge.

“I think they were always capable of it from a hull form standpoint, but there wasn’t the driver economically,” he said.

Advances in engine technology complement the design of the ECO class. Propulsion is provided by a MAN 6G50ME-B9.3 slow-speed main engine, producing 13,526 hp at 90.3 rpm (maximum continuous rating) and 7,744 hp at 82 rpm (normal continuous rating). The power plant was built at Doosan Engine, which also supplied three 1,240-kW auxiliary gensets for Magnolia State. Service speed is 14.5 knots.

|

|

The 610-foot product carrier, shown a week before delivery in May to American Petroleum Tankers, has a 330,000-barrel capacity. External piping systems reduce maintenance in the holds. |

“The G-series engines have a super-long stroke length, which for a big two-stroke engine just enables better efficiency,” Larson said. “They’re also electronically timed as opposed to having a camshaft, enabling better timing of fuel injection to the cylinder. All of those things combined leads to a more efficient engine and a more efficient ship.”

For future cost savings and flexibility, Magnolia State and its ECO-class sisters are built to allow a conversion to LNG propulsion. For NASSCO, that meant providing the necessary structural upgrades and space for LNG tanks and related systems.

“You would have to add all of the piping and new equipment, but we have the space and power on the ship already taking that into account,” Larson said. “You try to get the hardest things out of the way, like the structure. You don’t want to go into a shipyard retrofit having to rip out decks.”

A conversion to LNG also would require modifying the main engine, a process that would involve adding gas injection valves to the cylinder heads. But the addition and modification of equipment likely won’t hold back APT if it decides to make Magnolia State a dual-fuel ship. The driving factor will be the cost of liquefied natural gas versus conventional fuel.

|

|

Electronics on Magnolia State’s spacious bridge include a wide range of JRC components. |

APT President Rob Kurz said the company wanted the latest generation of product tankers when it went back to NASSCO to order new ships, and in the process it got dual-fuel capability. APT’s predecessor, U.S. Shipping Partners, took delivery of two State-class ships in 2009; subsequent vessels in the series were delivered to APT, a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan.

“Those ships have performed very, very well for us,” Kurz said. “As it relates to the LNG-conversion-ready option, it just made sense for us that we’ll have the flexibility to be able to do that at some point down the road.”

Conversion of the ships remains uncertain as the world’s energy markets continue to tread water at levels well below the norm three years ago. Kurz said the “whole amalgam” has been complicated by the dramatic reduction in the price of crude oil and the corresponding drop for other fuels.

“It’s really a classic cost-to-benefit analysis,” he said. “It’s difficult to make that kind of capital investment (for conversion) when the recovery of that capital investment is going to be difficult to achieve over a reasonable period of time. It really depends on the price of fuel.”

|

|

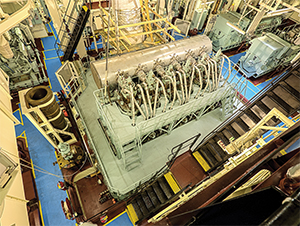

The MAN B&W slow-speed main engine delivers more than 13,500 hp. |

With any new technology comes a learning curve, but the one associated with building the ECO class has not affected delivery times. Larson said Lone Star State, the first ship in the series, was completed faster than any other tanker built at NASSCO, and the speed of the process was comparable for Magnolia State. The yard has previous experience in the world of LNG, having delivered the dual-fuel containerships Isla Bella and Perla del Caribe to TOTE Maritime during the past year.

“The first ship (in a series) is always the hardest,” Larson said. “Compared to the State class, we actually built these (ECO class) ships about two and a half months faster overall. That was challenging for us because 2015 was a big year for NASSCO. We processed 60,000 tons of steel through our yard, which is the most we’ve ever done.”

The technologies built into Magnolia State and its ECO-class sisters are already paying dividends in the Jones Act trade and promise to continue to do so for years to come. Although the original State class is less than a decade old, the new “States” have redefined efficiency for NASSCO tankers.

“That is really a testament to modern ship design and modern engine technologies,” Larson said. “They’ve really advanced that much in a short period of time.”